This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Resources Tag: CARBON MARKETS 101

New research on forest carbon leakage supports ACR’s approach

By Kurt Krapfl, PhD

By Kurt Krapfl, PhD

A highly anticipated peer reviewed publication on leakage in forest carbon projects, recently published in Environmental Research Letters, reinforces ACR’s existing approach as science-based and conservative. Continued research is needed to support the application of more precise and consistent approaches to leakage accounting across the market.

Leakage rates vary based on project factors

Leakage refers to the unintended increase in greenhouse gas emissions outside the boundary of a forest carbon project due to the project activity, such as reduced harvest levels, increased rotation lengths, or set asides.

The most recent publication on forest carbon leakage from Daigneault et al. (2025)1 used an economic modeling approach to examine leakage dynamics in forest carbon projects.

The paper has several important findings relevant to the carbon market.

The study confirms that forest carbon projects do not automatically lead to carbon leakage and in some cases may cause little to no leakage or even positive leakage (i.e., market spillover effects that spur investments in storing more carbon on the landscape).

The study also supports what many practitioners in the forest carbon market have anticipated for years – that forest carbon leakage varies based on project attributes. Despite this complexity, the carbon leakage rates in Daigneault et al. align well with the existing ACR leakage deductions.

The study also supports what many practitioners in the forest carbon market have anticipated for years – that forest carbon leakage varies based on project attributes. Despite this complexity, the carbon leakage rates in Daigneault et al. align well with the existing ACR leakage deductions.

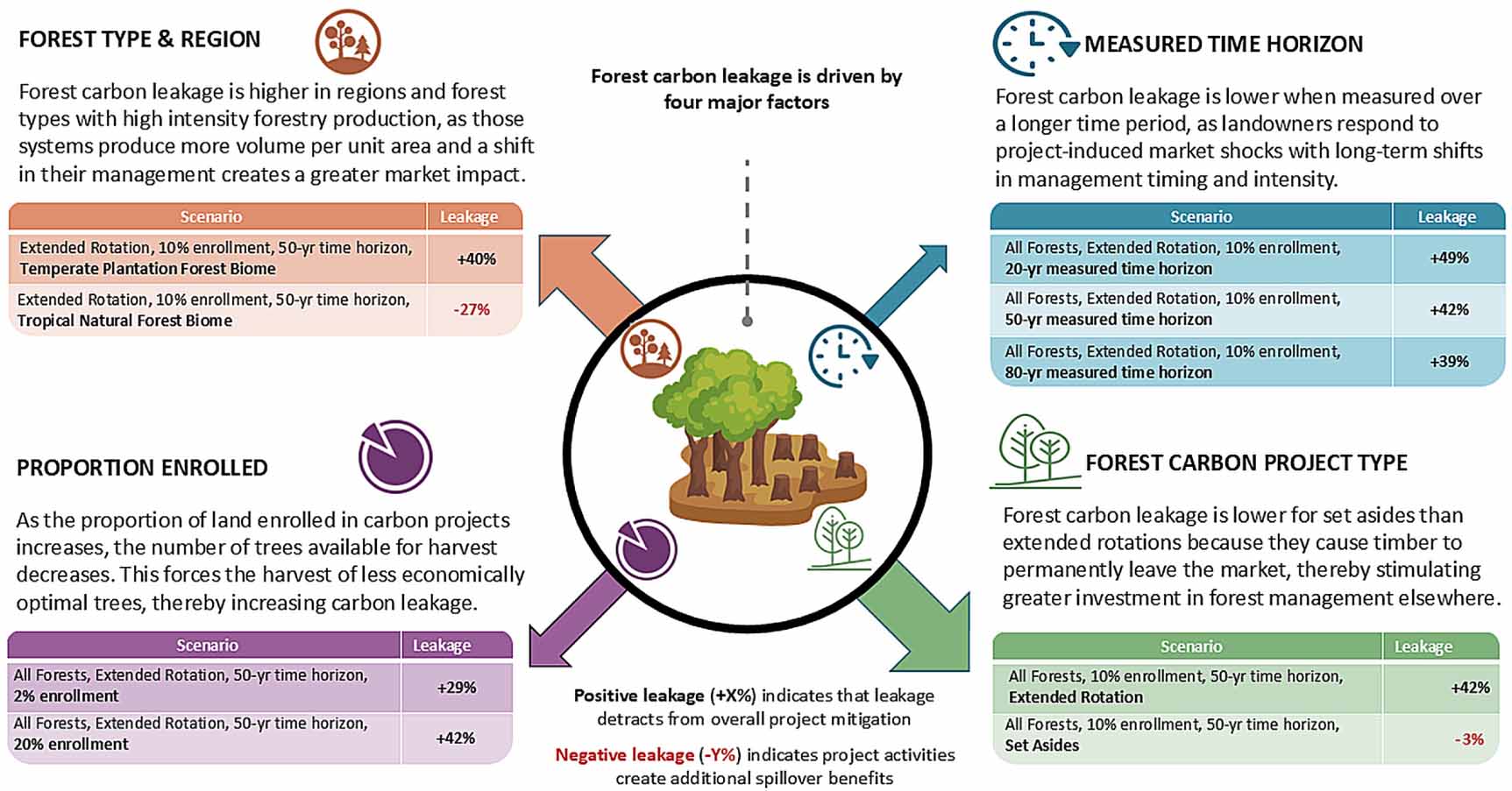

Figure 1, below, provides a succinct summary of the factors identified by Daigneault et al. as most influential to forest carbon leakage estimates.

Research aligns with ACR’s leakage deduction

ACR interpreted the forest carbon leakage estimates from Daigneault et al. in the context of our Improved Forest Management (IFM) methodologies, considering 1) ACR IFM operates primarily in the U.S., 2) ACR has projects incorporating varying levels of harvesting and forest types, and 3) ACR requires a legally-binding 40-year minimum project term for continued monitoring, reporting and verification.

A simple interpretation is below:

- Table S32 provides IFM leakage estimates for six U.S. forest types: Northern Hardwood, Northern Softwood, Southern Hardwoods, Southern Pine, West, and West Valuable Softwood. Acreages for each forest type are provided in Table S5.

- The current IFM implementation rate on eligible continental U.S. lands is approximately 3.2%3,4. Rounding up to a 5% implementation rate is conservative because it yields increased leakage estimates from the study (compared to the 2% implementation rate).

- Carbon leakage rates in the study are available for a 20-year average, a 50-year average, and an 80-year average. The 50-year average most closely resembles the ACR minimum project term of 40 years.

- For a 50-year forest carbon project at 5% implementation, a weighted average leakage estimate across U.S. forest types is 29.6% for extended rotation and -0.8% for set asides (or, a 14.4% total leakage rate, if combined).

In theory, application of set aside versus extended rotation could be assessed and applied at the project level. Leakage rates could also be assigned more precisely by region.

For simplicity, averaging across forest types and applying only the extended rotation leakage rate for all projects would provide a highly conservative estimate of ACR IFM forest carbon leakage at 29.6%. This aligns with the 30% leakage deduction to total crediting applied in the ACR IFM program today.

Conclusion

As crediting programs look to integrate the latest research into policy, the first step is naturally taking stock of how the results compare to the status quo. A first look reinforces ACR’s existing approach as science-based and conservative.

While the latest paper furthers our understanding of leakage, more research is warranted.

Because real-world forest management and leakage is dynamic, future research should examine the development of leakage estimates corresponding to fluctuating rates of harvest (as opposed to the categorical grouping of “set aside” or “extended rotation”). Recommendations on where and how leakage deductions should be applied in carbon accounting frameworks – such as to specific carbon pools like harvested wood or to credits issued overall – are also needed for ensuring leakage approaches are implemented appropriately and comparably across programs.

ACR is committed to ongoing review of our approach based on the latest scientific research and lessons learned. The latest findings on leakage confirm ACR’s approach as conservative and appropriate. The urgency of climate change demands that we continue to invest in climate action now.

Kurt Krapfl, PhD, is Director of Forestry at ACR.

Footnotes:

- Daigneault, A., Sohngen, B., Belair, E., Ellis, P. 2025. A globally relevant data-driven assessment of carbon leakage from forestry. Environmental Research Letters 20(11). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ae0ce2 ↩︎

- https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ae0ce2/data ↩︎

- As of January 2026 there are 7,756,907 acres of IFM projects registered in the continental U.S. (CONUS) under ACR (3,850,354 CARB, 17,781 ECY, 3,888,772 ACR). A conservative doubling of this value to encompass IFM projects registered under CAR and VCS (which we know to be highly conservative) would result in an estimated 15,513,814 acres registered in IFM projects in the CONUS. From FIA data, there is 678,389,782 acres of CONUS forestland and 489,361,771 acres excluding federal ownership (https://apps.fs.usda.gov/fiadb-api/evalidator). 15,513,814 IFM acres / 489,361,771 eligible acres = 3.2% Implementation Rate. ↩︎

- Alaska and Canada currently have relatively lower IFM uptake on a per acre basis relative to CONUS, such that it is conservative to omit these regions from this analysis and reduce the denominator used to calculate implementation rate and thereby arrive at higher estimated carbon leakage rate from the study. ↩︎

ACR’s Approach to Non-Permanence Risk Mitigation

Not only is the protection, conservation and restoration of forests critical to meet the Paris Agreement climate targets, but these actions are also among the most readily deployable, affordable and scalable available today.

Forests store 861 billion tonnes of carbon (source) and sequester 7.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide annually (source), which represents approximately 20% of total global emissions. Research has shown that forests and other nature-based solutions to climate change have the potential to sequester one-third of global emissions annually (source).

At ACR, we often get asked about “permanence” of forestry projects and how we can effectively mitigate the risks of sequestered and credited carbon being re-released to the atmosphere.

ACR has robust, enforceable systems in place to mitigate non-permanence risks to ensure the integrity of the credits ACR issues.

Carbon market “permanence” and “reversals”

In the context of carbon markets, “permanence” refers to the perpetual nature of emissions reduced or removed from the atmosphere and the risk that the atmospheric benefit will not be permanent. This risk is not relevant for some project types for which the emission reductions or removals are permanent once they occur and cannot be reversed (such as in a project that destroys refrigerants).

In forestry and other nature-based projects (also known as “Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use” or AFOLU), there is an inherent potential for emissions to be re-released into the atmosphere. When carbon associated with previously issued credits is re-released to the atmosphere prior to the end of a carbon project term, it is termed a “reversal.” Reversals can result from unintentional events occurring prior to the completion of a project, such as fires, pests, diseases, or floods, or through intentional actions, such as forest conversion or overharvesting. In these cases, well-designed risk mitigation mechanisms can ensure that any potential re-emission is quantified and compensated for to maintain the integrity of issued carbon credits and the fungibility in the market with offset credits that do not have reversal risk.

Projects registered with ACR must commit to measure, monitor, report, and verify (MRV) the project activity for a legally binding minimum project term of 40 years. This meaningful project timeframe is aligned with scientific reports that have assessed the critical role of the AFOLU sector in all 1.5°C-consistent pathways to achieve Paris Agreement targets and reach net zero emissions by mid-century.

At ACR, reversals must always be reported, quantified, and compensated, to maintain the integrity of the credits ACR issues. However, ACR has separate and specific mechanisms to address unintentional and intentional reversals.

ACR manages a diverse buffer pool for unintentional reversals

Reversals attributed to natural disturbances are considered “unintentional;” when they occur, they are compensated for by cancelling credits from the ACR Buffer Pool.

ACR requires that prior to each issuance, projects with reversal risk undertake a comprehensive reversal risk analysis via the ACR Risk Tool (with an updated version under development). The result of the analysis is a volume of credits that must be deposited (i.e., “Buffer Pool contribution”) to a reserve account managed by ACR and held for the sole purpose of unintentional reversal compensation. The buffer pool approach to unintentional reversals works similarly to an insurance mechanism where all participants contribute but few make claims.

The ACR Buffer Pool balance represents approximately 20% of credits issued from ACR projects that require a Buffer Pool contribution to compensate for unintentional reversals.

ACR allows buffer pool contributions from a variety of project types, including forestry, grasslands, transportation, refrigerants and industrial projects, like landfill gas. Similar to any risk mitigation mechanism, diversity in the makeup of this pool adds resilience. A larger and more-diverse credit pool, in terms of geography, project type, and reversal risk, is better.

Many of the credits in the ACR buffer pool are permanent emission reductions (i.e., credits that do not carry a risk of reversal). Including non-reversable credits in the buffer pool is a conservative and environmentally robust approach, especially in the context of mitigating large and widespread natural disturbances. Because the ACR Buffer Pool is managed across the entire AFOLU portfolio, the inherent diversification adds further assurance and stability to this mechanism for reversal risk mitigation.

It is important to note that ACR has yet to experience an unintentional reversal from its AFOLU portfolio (nearly 80 projects) that required compensation from the Buffer Pool. Many ACR projects are large and geographically and ecologically diverse. As a result, only the most catastrophic disturbances would cause reversals. Small and localized disturbances that may occur are typically overcome by annual forest growth; they do not cause overall carbon stocks to decline during the reporting period to the extent that it would constitute a reversal. In addition, ACR has a large and growing volume of credits issued to aggregated or programmatic projects, which by definition have a wide geographic spread and inherent diversity, decreasing the likelihood of a single catastrophic event causing a reversal.

While it is unlikely, if the quantified volume of an unintentional reversal were to exceed the cumulative buffer contributions from the project, ACR would assess a penalty in the form of an additional buffer contribution and replace the remainder of the outstanding balance from the Buffer Pool.

If ACR has to cancel credits in the Buffer Pool due to an unintentional reversal, ACR will refer to the following set of criteria in determining the cancellation of Buffer Credits for relevant reversal events:

- Reversals for CORSIA Eligible carbon credits will be compensated with CORSIA Eligible carbon credits in the Buffer Pool.

- Reversals for projects that contributed AFOLU credits will be compensated with AFOLU credits in the Buffer Pool.

- Reversals for projects that contributed non-AFOLU credits will be compensated with credits with a vintage within 5 years of the affected GHG Project start date in the Buffer Pool. If there are none or if the full amount does not fit this criterion ACR will select from the most recent vintages available.

As an additional conservative measure, ACR does not refund Buffer Pool credits. At the end of the project’s crediting period, ACR cancels an equivalent volume of unused buffer pool contributions to compensate for potential future reversals.

Project proponents must fully compensate for intentional reversals

Reversals attributed to management decisions and other willful activities – such as over-harvesting, forest conversion, or discontinuing MRV before the end of the minimum 40-year project term (Early Project Termination) – are considered “intentional” by ACR.

For intentional reversals, ACR requires that the project proponent compensate for all credits associated with the carbon loss event by replacing those credits for cancellation by ACR. For Early Project Termination, this includes compensation for all credits that have ever been issued to the project. This commitment is solidly reinforced with a legally binding contractual agreement, signed by the project proponent prior to carbon credit issuance.

Legally binding contractual agreements, if possible, are the strongest mechanism to mitigate the risk of intentional reversals from projects.

Protecting, restoring and sustainably managing forests is essential to stay on track to meet Paris Agreement climate targets. ACR has strong, legally enforceable systems in place to mitigate reversal risks of forestry projects, which ensures the integrity and fungibility of the credits we issue.

High GWP Pollutants

High GWP Pollutants

By: Megesh Tiwari – Senior Technical Manager, American Carbon Registry

ACR’s Carbon Market 101 blog series explores and explains carbon markets and how ACR tackles various issues in our ongoing mission to set the bar for carbon credit quality.

At ACR, we have a strong focus on incentivizing actions to reduce and eliminate extremely potent non-CO2 climate pollutants like methane, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), and ozone depleting substances (ODS) like chlorofluorocarbons (CFC) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFC). Given the potential to deliver significant climate impact, we thought it would be useful to introduce some of the central concepts associated with our innovative and industry-leading methodologies for refrigerants, foam blowing agents, ozone depleting substances, landfill emissions, and orphaned and abandoned wells.

What is Global Warming Potential?

To better understand the impact that different greenhouse gasses (GHG) have gasses have in contributing to the rise in the Earth’s temperatures, scientists established the concept of Global Warming Potential (GWP).

The GWP compares the emissions of one metric ton of different GHGs against the emissions of one metric ton of carbon dioxide (CO2) over a given period of time, most commonly over 100 years. GWP is a relative term and is calculated by dividing absolute GWP of a GHG by absolute GWP of CO2. As such, CO2 is the reference GHG with GWP value of 1. The higher the GWP value, the more it contributes to global warming. For instance, if a pollutant has a 100-year GWP value of five, it contributes to global warming at a rate of five times higher than CO2 over the period of hundred years from the date the pollutant was released into the atmosphere.

What are short-lived climate pollutants (SLCP)?

Another important distinction in comparing harmful pollutants is distinguishing short-lived GHGs from long-lived GHGs. For instance, CO2 can last for centuries in the atmosphere before breaking down, while methane, which has a high GWP, remains in the atmosphere for a much shorter period – only around a decade.

It takes 100 years for around 60-70% of the carbon dioxide to decay in the atmosphere. The rate of decay decreases over time, taking around 500 years for the additional 10% CO2 to decay and over thousands of years for all CO2 to decay. However, in the case of short-lived climate pollutants, like methane, HFCs and HCFCs, over half of the decay happens within first 20 years. In other words, these short-lived GHGs heat the atmosphere at a much higher rate in the initial years after their release, several times higher than their 100-year GWP values. For example, even though HCFC-22 (the most commonly used refrigerant in refrigeration and air conditioning) traps heat around 2,000 times more than CO2 over 100 years; but in the first 20 years, it traps heat around 5,000 times more than CO2. Because of these alarmingly high heat trapping properties, reducing emissions from these short-lived pollutants is critical for avoiding rapid warming of the planet in the short term.

Where are high GWP pollutants used?

High GWP pollutants are present in hundreds of manufacturing, industrial and agricultural processes. High GWP pollutants are often paid less attention than CO2 emissions, but they make a significant contribution in the rise of global temperatures. Global phaseout of HFCs can alone prevent 0.5C warming of the planet by 2100.

Methane, which has a GWP of between 27 and 30 over a 100-year period, is often found in agricultural production (which accounts for 23 percent of U.S. methane emissions), landfills (17 percent), and oil and natural gas operations (30 percent).

HFCs and perfluorocarbons (PFCs) – which can have GWP in the thousands – are used in a wide variety of applications, including air conditioning units, refrigerators and foam insulation.

HCFCs, which are also ODSs, were the most widely used compounds for refrigeration, air-conditioning and foam insulation before they were started to be phased out in 2020 in the US. However, many other countries have not yet begun to completely phase out use of HCFCs. And even in countries where HCFCs are being phased out, the market for recycled and reclaimed HCFCs in still huge, especially to service existing equipment. On top of this, even as old equipment gets replaced with new equipment that uses lower GWP alternatives, the remaining gas sits in stockpiles and eventually vents into the atmosphere.

What can be done to limit the use of high GWP pollutants?

Some groups of pollutants have been targeted by governments and international bodies and are strongly regulated or banned. For instance, the Montreal Protocol, which was ratified by all 198 United Nations Member States, calls for the phasing out of ODS, which are also high-GWP climate pollutants, through target dates and strong reporting measures.

But other high GWP GHGs like HFCs and methane are still present in hundreds of manufacturing, industrial and agricultural processes And while production and consumption of virgin HCFCs are banned in the US, the market for reclaimed HCFCs to service old (leaky) existing equipment is still robust.

Carbon markets can incentivize projects that remove or avoid the release of GHG emissions into the atmosphere. Revenue generated from carbon credits allows for the collection and safe destruction of these harmful pollutants, along with financing the transition to alternatives that contribute less to global warming.

For example, in the case of refrigerants, air conditioners and foam insulation, there are often low-GWP alternatives that already exist. Unfortunately, many of these alternatives are cost prohibitive and have not been widely adopted in the marketplace. Carbon markets can play a role in supporting industries to transition more quickly to low GWP alternatives.

The destruction of, and transition away from, these high GWP GHGs is irreversible, permanent and fully additional and has significant short-term impact on preventing global temperature rise. It is expected that as more companies continue to signal interest in purchasing these kind of carbon credits, the price of the credits will rise, creating more revenue for projects and catalyzing wider adoption of alternatives.

Examples of ACR methodologies focused on high-GWP, short-lived climate pollutants

Advanced Refrigeration Systems, version 2.1

Certified Reclaimed HFC Refrigerants, Propellants, and Fire Suppressants, version 2.0

Destruction of Ozone Depleting Substances and High-GWP Foam, version 1.2

Destruction of Ozone Depleting Substances from International Sources, version 1.0

Transition to Advanced Formulation Blowing Agents in Foam Manufacturing and Use, version 3.0

Capturing and Destroying Methane from Coal and Trona Mines in North America, version 1.1

Landfill Gas Destruction and Beneficial Use Projects, version 2.0

Plugging Abandoned & Orphaned Oil and Gas Wells, version 1.0 (in scientific peer review)

Additionality and Baselines for Improved Forest Management Projects

Additionality and Baselines for Improved Forest Management Projects

By Kurt Krapfl, PhD – ACR Director of Forestry

Demand for voluntary carbon credits is expected to grow in response to the urgency of climate change. Much of this demand is driven by the increasing number of companies seeking to decarbonize their supply chains and use high-quality carbon credits to offset residual emissions. To address questions we receive, ACR developed this blog post focused on additionality and baselines in Improved Forest Management projects.

ACR IFM Additionality and Baselines

Some of the questions ACR is frequently asked are about “additionality” and baseline setting for Improved Forest Management (IFM) projects.

How do we ensure that project actions or policies exceed those that would have occurred in the absence of the project activity and without carbon market incentives? How do we ensure a credible baseline scenario from which to measure performance?

The following explains ACR’s approach and how our IFM methodology addresses common questions around assessing additionality and establishing a conservative baseline.

IFM Background

In the U.S., the number of IFM projects in development is growing because standards bodies like ACR have published methodologies that are applicable to a variety of landowner types, including private industrial, private non-industrial, tribal, public non-federal, and non-governmental organizations. By attaching a monetary value to carbon sequestration, the carbon market presents an opportunity for different types of landowners to achieve a higher standard of forest management, while still supplementing their revenue goals and helping to combat climate change.

It is important to note that enrollment in an ACR IFM project initiates an immediately effective, legally binding, and public-facing 40-year commitment to grow trees older and larger, and/or to harvest less frequently or intensely. The projects quantify and credit carbon stored on the landscape as a result of this new long-term management commitment. IFM offers a cost-effective and scalable opportunity to sequester carbon now, as we pursue a transition to a net-zero economy by 2050.

Additionality

Key to ensuring the credibility of carbon credits is the concept of additionality. This assumption is a central tenet of all carbon crediting programs and projects, not just IFM. It is important because there needs to be a high level of confidence that project actions or policies exceed those that would have occurred in the absence of the project activity and without carbon market incentives.

The ACR IFM methodology contains specific requirements for project proponents to demonstrate additionality. As a first step, all ACR IFM projects must be verified to meet a 3-prong additionality test, requiring demonstration that they: 1) exceed all currently effective laws and regulations; 2) exceed common practice management of similar forests in the region; and 3) face at least one of three barriers to their implementation (financial, technical, or institutional).

The regulatory surplus test involves evaluating all existing laws, regulations, statutes, legal rulings, deed restrictions, donor funding on allowable management activities, contracts, or other regulatory frameworks relevant to the project area that directly or indirectly affect GHG emissions associated with a project action or its baseline candidates, and which require technical, performance, or management actions. The project action cannot be legally required.

The common practice test requires an evaluation of the predominant forest management practices of the region and a demonstration that the management activities of the project scenario will increase carbon sequestration compared to common practice. This involves evaluating and describing the predominant forest management practices occurring on comparable sites of the region and demonstrating that the project activities will achieve greater carbon sequestration than in the absence of the project.

Finally, the implementation barrier test examines factors or considerations that would prevent the adoption of the practice or activity proposed by the project proponent. IFM projects often demonstrate a financial implementation barrier because carbon projects are generally expensive to implement and coincide with harvest deferral and forgone potential revenues. This results in a low internal rate of return in comparison to the land potential that dissuades many landowners from implementing carbon projects. Technological and institutional barriers associated with carbon projects may also be proposed.

Determining Baselines

Enhancing carbon stocks above a baseline scenario is the basis of carbon credit generation. Ensuring a reasonable baseline is equally important for ensuring credibility. Under ACR’s IFM methodology, determining the baseline involves a comprehensive assessment of site characteristics and constraints to forest management, as well as an analysis of predominant forest management practices occurring in the region, to develop an alternate forest management scenario that could reasonably be expected to occur in the absence of the project.

ACR baselines consider all legalconstraints to forest management, as well as operational constraints such as site access, mill capacities, hauling distances, and any other potential third-party approvals necessary to perform such activities. Baseline silvicultural treatments must be substantiated by attestations from regional professional foresters, peer-reviewed or state/federal publications, or written attestations from an applicable state or federal agency. Baseline harvest intensities (i.e., rate of baseline harvest) must be substantiated by geospatial analysis of harvests occurring on similar nearby lands, an approved forest management plan, or by demonstrating ability to harvest and setting a “removals-only” baseline. In other words, they need to be substantially vetted and validated by independent sources as both possible and plausible.

Finally, to systematically address the various management objectives and considerations confronting ownerships of different types, ACR IFM leverages a financial analysis considering recent forest inventory data from within the project area, timber prices, logging and management costs, and the time value of money in determining the baseline harvest schedule. NPV discount rates, in addition to the suite of baseline constraints identified above, add another layer of conservatism in setting the intensity and temporal distribution of the baseline on specific characteristics and motivations of an ownership.

The ACR approach is a consistent, replicable, and verifiable approach upon which to assess the various operational and feasible management decisions and trajectories facing U.S. forestland ownerships. Its method provides a transparent and systematic process by which landowners, project developers, verifiers, and offset purchasers can set and assess the ACR IFM carbon project.

As a leading carbon crediting program, ACR takes pride in ensuring projects using our methodologies generate carbon credits that are additional to business-as-usual and meaningful to the climate, both in the near and long-term.

We also recognize the complexities of this space and provide responses to commonly asked questions below:

Why Not Use Historical Baselines?

Historical harvesting activity does not necessarily represent a future management trajectory. This is because in the absence of an abrupt paradigm shift, silviculture and forest management occurs and evolves over long timeframes as trees grow and forest conditions change. Forest management is long-term and cyclical, and decisions are based on financial needs, market conditions, landowner and agency priorities, and other factors. Land can be sold and harvested and plans for how a forest is intended to be managed can, and invariably do, change.

Recent harvests on properties of similar site conditions and merchantability can, however, be indicative of the degree to which a given landowner could reasonably manage their forestlands. ACR terms this “Harvest Intensity” and leverages this information to set a conservative maximum baseline harvest threshold. Existing forest management plans may also be used to determine harvest intensity where they have been prepared by a qualified professional forester and contain explicit harvest thresholds.

Shouldn’t Project Proponents Justify the Baseline?

Yes. In addition to the requirement for ACR IFM projects to verifiably demonstrate that they exceed all currently effective laws and regulations, exceed common practice management of similar forests in the region, and face at least one of three implementation barriers, project proponents must also develop a baseline through a comprehensive assessment of site characteristics and predominant forest management practices relevant to the project area.

ACR baselines must consider all legal constraints to forest management, as well as physical constraints such as site access and operability, mill capacities, and hauling distances. They must justify plausible forest management practices that would occur in the absence of the project, including silvicultural prescriptions and harvest intensities. ACR requires the details of these analyses to be included in the GHG Project Plan and all baseline assumptions are third party verified and approved by ACR prior to each issuance.

Isn’t it possible that the forests in question would be managed the same way with or without carbon crediting?

Enrollment in an ACR IFM project represents an immediate change from previous practice because it initiates a legally binding and public-facing commitment to increase carbon stocks in the project area for 40 years. It is a tangible and immediate action to increase and quantify carbon sequestration according to a peer-reviewed scientific framework.

It is not common for a landowner with mature timber to make a long-term commitment (40 years in this case) to reduced harvesting and to legally forgo the opportunity to do so. As mentioned above, forest management is long term and cyclical based on financial needs, market conditions, ownership priorities, mill conditions, and other factors. Harvest intensity safeguards and dynamic evaluation over time ensure the baseline remains representative prior to each credit issuance.

Does the project take the most aggressive harvest scenario off the table?

Yes, although carbon projects do much more than just take the most aggressive scenario off the table. Projects enrolling with ACR must maintain or increase their forest carbon stocks over the 40-year project commitment term (i.e., they cannot harvest more than accumulated annual growth). Doing so would be a reversal and they would have to compensate ACR for the reversed credits. It is not common practice for a landowner with mature timber to enroll in a long-term, legally binding agreement that limits their capacity to harvest over time.

What about different kinds of landowners?

In the early days, the primary participants in IFM projects were large timberland owners. Over time, the market has expanded to include many different types of landowners. Evolving financial needs, market conditions, management priorities, and other factors are applicable to all kinds of landowners. Therefore, ACR’s criteria for additionality and determining baselines apply to all project proponents, who must justify why the baseline is a realistic management trajectory for their type of ownership. Organizations that may have longer-term, institutional climate targets should also factor these into their decisions to enroll IFM projects and their justification of baseline scenarios. The ACR methodology considers landowner type in assessing both harvest intensity of comparable properties and financial discount rate.

How does ACR improve its methodologies over time?

All ACR methodologies undergo a rigorous approval process that involves internal review, public consultation, and blind scientific peer review. ACR is the only registry to require scientific peer review for the approval of its methodologies.

We are continually updating and improving our methodologies over time. The ACR IFM methodology, for example, was first approved in 2010 and is undergoing its sixth version update. The new IFM version 2.1 provides clarifications and updates to increase the precision of the methodology, reflecting our deep knowledge base gained from implementing IFM projects for nearly 15 years.

ACR’s current IFM methodology version 2.1 was published in July of 2024.

Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines Enhance Precision in IFM

By: Kurt Krapfl

Improved forest management (IFM) has the potential to sequester an additional 267 million tonnes CO2e in forests of the United States, second only to reforestation among natural climate solutions[i]. IFM offers an important way to fund forest resilience and restoration work, such as fuel breaks, thinning, or balancing of age classes, while also reducing and removing carbon emissions.

ACR is the leading carbon crediting program for North America, with IFM projects covering over 8 million acres of forestland in the U.S. and Canada.

ACR first introduced its IFM methodology in 2010, and seven updates later, the newly released IFM version 2.1 increases the precision of its requirements for developing and evaluating conservative baseline scenarios.

Key takeaways about ACR’s updated IFM methodology include:

- The updated IFM methodology is fundamentally the same workable approach that has been applied to millions of acres of forests across the United States and Canada, incorporating over a decade of experience and leveraging the availability of new technology.

- The updated IFM methodology meets market expectations for quality through enhanced requirements for rigor and precision.

ACR achieved these objectives related to workability and precision through a couple key innovations:

- A baseline setting and updating process where key parameters are calculated with robust assumptions ex ante (up front) and verified ex post (after the fact), prior to each credit issuance.

- A systematic deep dive into the specific conditions of each property to understand the ability and intent of a landowner to harvest timber.

The quantity of credits issued to a carbon project is based on the difference in carbon stored between business-as-usual management (i.e., the “baseline”) and with-project management. As a result, setting high-integrity baselines is an extremely important component of carbon crediting.

ACR has been thoughtful and responsive in regularly refining our IFM approach based on lessons learned from implementation and demonstrated best practices. We strive for high-quality.

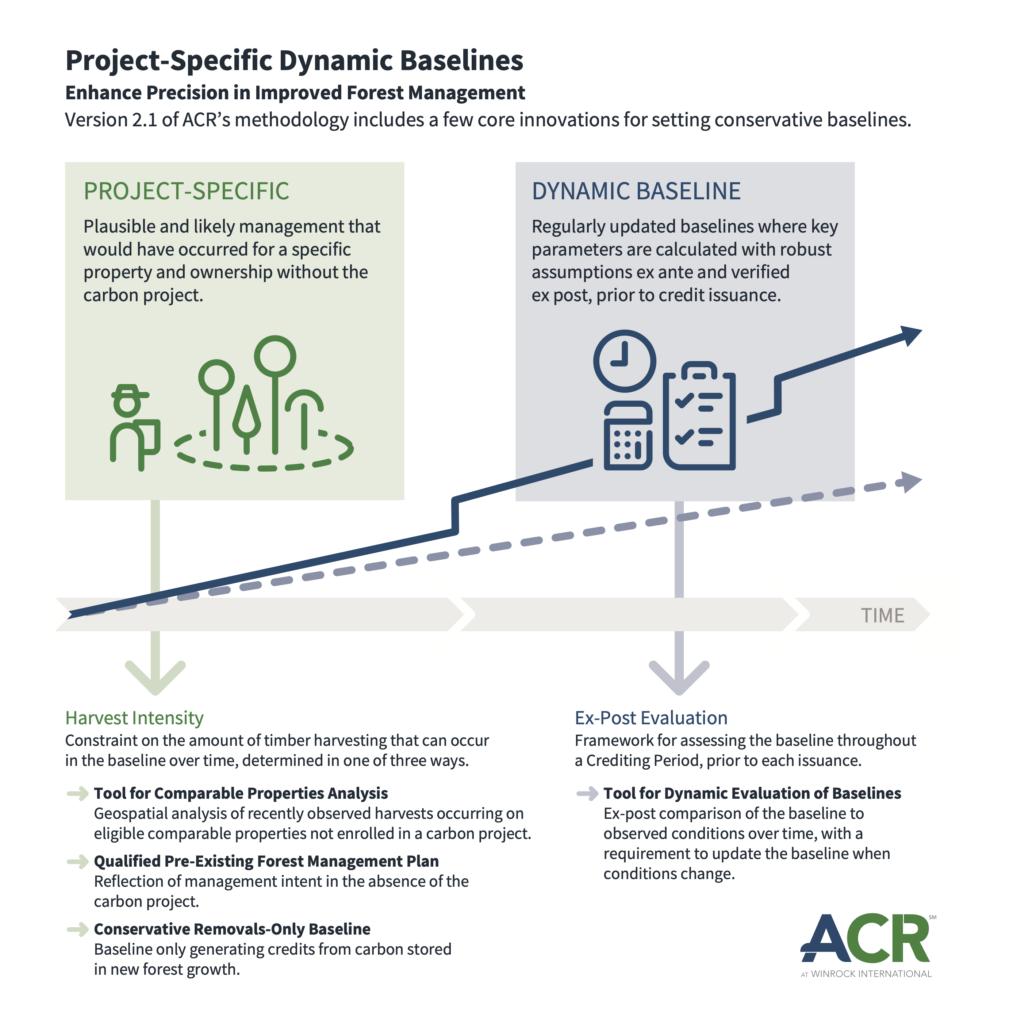

This article focuses on a few of the core innovations in the recent update to our methodology as they relate to a key concept, Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines.

ACR’s Approach to Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines

ACR Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines use information derived from the project area to set a precise and conservative carbon crediting baseline. The approach requires projects to reassess and update baselines as necessary – prior to each credit issuance.

“Project-specific” emphasizes the plausible and likely management scenario that would have occurred for a given property and ownership, had the carbon project not been undertaken.

This requires detailed information regarding the ability and intent of a landowner to harvest timber. For example, a nonprofit land trust is likely to have a different intent for its property compared to a forest management company; the baseline should reflect those differences. Similarly, a landowner without merchantable or accessible trees shouldn’t be credited for deferring a harvest that could never feasibly occur. ACR’s approach requires a comprehensive evaluation into the specific conditions of each property to provide the details needed to understand the plausible and likely baseline scenario.

“Dynamic” emphasizes a baseline that is regularly updated to reflect changing conditions over time. The ACR IFM baseline is calculated with robust assumptions ex ante and is confirmed and updated ex-post on the basis of observable, pre-determined parameters relevant to forest management. While “dynamic baselines” have been proposed in the carbon market across a variety of contexts, the ACR approach was designed to reflect changing conditions and increased ambition over time. ACR IFM baselines are evaluated prior to each issuance to confirm the baseline remains relevant and accurate across the lifetime of the project.

The latest iteration of the ACR IFM methodology implements this approach with two important updates: 1) a new “dynamic evaluation” of baselines over time; and 2) the addition of “harvest intensity” as a constraint in baseline setting. These updates are presented below.

Reflecting Changes on the Ground

Carbon credit buyers have signaled a desire for more frequently updated baselines. This raises a challenge in balancing the certainty needed for attracting upfront investment for landowners to commit to long-term harvest management practices with the flexibility necessary to modify baselines when conditions change. The ACR IFM methodology embraces this balance in a practical way to produce high-precision, high-impact carbon credits.

To determine if a project baseline must be updated, ACR developed the Tool for Dynamic Evaluation of Baselines. The tool establishes a framework for assessing the baseline throughout a Crediting Period on an ex-post basis, prior to each credit issuance.

At each Reporting Period verification – full and desk-based – an ex-post comparison of the baseline scenario to recently observed conditions is conducted. The comparison is implemented as a practical checklist which assesses key parameters, requiring projects to demonstrate that baseline assumptions and harvest rates align with relevant observed legal, physical, and economic conditions. If parameters have changed significantly, the baseline is adjusted prior to credit issuance.

In addition, for each Reporting Period subject to full verification, occurring no less frequently than every five years, a complete reassessment of the long-term modeled baseline scenario is also conducted and modeled projections are refreshed and re-parameterized.

Importantly, ex-ante projections do not define the baseline scenario for crediting purposes. ACR only issues ex-post credits, following an assessment of modeled versus observed conditions at each verification preceding credit issuance.

Setting a Precise and Conservative Baseline

All ACR IFM projects must conduct a robust forest inventory to help determine the baseline. Foresters assess the conditions of the property, physically measure trees, and summarize the available forest resources. Only merchantable and accessible trees may be considered for harvest in the baseline. All baseline harvests must be legally, physically and financially feasible, factoring in specific costs and logistics relevant to the property. Simply put, there is no substitute for boots-on-the-ground observations and data.

Projects then develop a realistic and likely forest management trajectory that would occur in the absence of the project, which involves two steps. First, projects must specify silvicultural prescriptions that are common practice for the region and appropriate and likely for the project area, given its species mix, terrain, and other characteristics. These prescriptions must be substantiated by a local forester.

The projects then calculate harvest intensity, which is a constraint on the amount of harvesting that can occur in the baseline over time, expressed as the maximum percent biomass removed per acre per year. Essentially, the baseline can only be as aggressive as the observed harvest intensity occurring on nearby comparable properties with similar characteristics and land ownership type, but not enrolled in a carbon project.

Ultimately, there are many factors that may impact the volume and type of forest products a landowner would harvest, and they may change over time. Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines consider forest conditions, site access and operating costs, mill access and capacity, legal conditions, and more, to provide the best possible information for assessing what a landowner would most likely do in the absence of the carbon project. This is all vital to establishing a credible and conservative baseline.

Harvest intensity conservatively ensures that baselines reflect variables that are otherwise hard to measure, such as landowner intent and broader market conditions. The approach requires Project Proponents to prove out baseline harvesting levels, while also safeguarding against unrealistically aggressive baselines.

Calibrating Baseline Harvest Intensity

The ACR Tool for Comparable Properties Analysis prescribes a detailed geospatial analysis for calculating harvest intensity from recent observed harvests occurring on similar properties in the region that are not enrolled in a carbon project. Projects may use publicly available, pre-approved harvest detection data sources, or may propose an internally developed and calibrated remote sensing model if accompanied by a demonstration of increased precision in comparison to the pre-approved approach.

To conduct a comparable properties analysis, eligible properties are identified using cadastral data (i.e., tax parcel boundaries) and eligibility criteria. Eligible comparable properties must be of a similar size and forest cover class as the project and be located within a 150-mile radius. They must also have a similar ownership structure (non-profit, public, private industrial, family forest owner, etc.). Eligible comparable properties are stratified by forest type, and their recently observed harvests and forest conditions are mapped using remote sensing.

ACR then requires projects to systematically evaluate each property across seven key parameters, including property size, distance to the project area, slope and elevation, aboveground biomass density and merchantability, and forest type. A similarity index ranks the comparable properties, and the eight most similar are considered “matched.”

Matched properties are then subjected to an outlier detection test, and of the remaining matched comparable properties, one is selected as a representative harvest constraint. This means that baselines may only be as aggressive as the observed harvest intensity occurring on the most similar nearby properties, within a recent lookback period, that are not enrolled in a carbon project.

In addition to the comparable properties analysis, the ACR IFM approach also includes two additional pathways to set harvest intensity: a qualified, pre-existing forest management plan, or a conservative removals-only baseline.

Qualified, pre-existing forest management plans must have been prepared by a professional forester prior to carbon project development, reflecting management intent in the absence of the carbon project. The qualified management plan must contain specific recommendations for the spatial extent or volume of biomass to be removed over time. These recommendations are used as a maximum baseline harvesting constraint.

Removals-only baselines must develop and validate a baseline harvest schedule, considering all constraints to forest management. If the modeled baseline harvests more than growth, the baseline is conservatively set at initial carbon stocks. If the resulting baseline harvests equal or less than growth, the modeled baseline can be used. As the name suggests, removals-only baselines do not generate emission reductions credits (only removals) and must conservatively be held at initial carbon stocks or increasing.

With ACR IFM projects covering millions of acres of forestland in the U.S. and Canada, including small family woodlands and tribal lands, it is important to give landowners options, especially for an innovative approach.

Whether through the comparable properties analysis, qualified forest management plan, or removals-only baseline, the harvest intensity constraint establishes an accurate and conservative baseline.

Conclusion

To achieve the Paris Agreement goals, carbon markets must grow. To grow, carbon credit buyers demand high integrity, while landowners and project developers require practicality and predictability before signing an agreement that legally binds their forest management for a minimum of 40 years. Since an independent carbon crediting program is only as beneficial as it is used, ACR’s job is to find the right balance between these interests.

ACR Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines represent this balance. They are set based on observed management occurring on similar, nearby lands that are not enrolled in a carbon project. Baselines are updated over time to reflect observed conditions changing in the project area and surrounding landscape. And they are regularly reassessed to ensure ongoing validity prior to issuing credits at each verification.

The ACR Improved Forest Management Methodology version 2.1 represents the latest iteration of our widely used approach to promote sustainable management of forests above common practice.

Through this approach, ACR provides landowners with a meaningful and practical way to manage their lands with climate at the forefront. Hundreds of landowners are already enrolled in IFM carbon projects with ACR. These landowners have realized the benefits of embracing carbon as an amenity and revenue stream that can finance their long-term forest management objectives.

As the leader in North American IFM, ACR has continually set the bar for quality in the market. Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines now move the market a step further in ensuring conservative and data-based IFM carbon crediting.

ACR looks forward to continuing our work with landowners, project developers, credit buyers, and the market overall in incentivizing the climate benefits needed to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement and ensure a stable, livable climate.

July 2025: ACR posted an explainer video for application of dynamic baselines under ACR’s U.S. IFM methodology v2.1.

July 2025: Projects listed under previous versions of ACR’s U.S. IFM methodology and Canadian IFM methodology can now optionally use the Dynamic Evaluation of Baselines Tool version 1.1 to perform dynamic baseline evaluations on a go-forward basis.

On September 19, 2024, we hosted a webinar about ACR Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines. If you would like to watch it, a recording is available here and you can download the slide deck here.

Kurt Krapfl is forestry director at ACR.

[i] Fargione et al., 2018. Natural climate solutions for the United States. Science Advances 4(11). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aat1869