This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Resources Tag: PRIMER

Orphaned Oil & Gas Wells

What is the challenge?

The oil and natural gas industry has been drilling wells for more than 160 years, leaving a legacy of unplugged wells that can have acute and chronic environmental impacts. Orphaned wells are unplugged wells that no longer have a responsible operator. Many of these wells have fallen into advanced states of disrepair and are often leaking methane when left unplugged or are improperly plugged. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that orphaned and abandoned wells emit an estimated 7-20 million or more metric tons (MT) CO2e per year, though the actual number may be much larger. Methane is a highly potent GHG with immediate negative impacts after it enters the atmosphere, therefore addressing methane emissions associated with orphaned wells will have an early positive impact on the climate. This benefit is an addition to helping address a wide range of other environmental concerns, including the potential pollution of groundwater, emission of toxic gases blended with methane, and potentially deadly gas blowouts from unplugged or improperly plugged wells.

A number of challenges exist in addressing the issue:

We don’t know how much we don’t know. It is acknowledged that the EPA is vastly underestimating the size of the problem – both in the number of wells, which can be difficult to locate, and associated methane emissions. One of the main factors contributing to this potential underestimation is that the total population of orphaned oil and gas (OOG) wells is still unknown. Estimates in EPA reports cite 2.3 to 3.2 million orphaned and abandoned wells. But new research suggests the problem is likely to be many times larger. For example, Dr. Mary Kang, a leading researcher on orphaned wells at McGill University, and other scientists who have studied OOG wells in the U.S. note that in Pennsylvania alone, the number of these wells is as high as 750,000. Wells are also present in large numbers in other oil producing states such as Texas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana. It is also unclear how much methane these wells are leaking- generally the emissions are dominated by high-emitting wells, which ACR’s methodology prioritizes for plugging. The problem may only grow more severe in time as more wells drilled decades ago reach their expected end of life and could easily become OOG wells. Most wells are expected to have a 30-year operation timeframe and the peak of active drilling rigs creating wells occurred from 1980-1985 in the United States.

Regulation exists, but in many cases it is insufficient to address actual plugging costs and environmental concerns. In addition, challenges in enforcement and significant opportunities for operators to delay plugging are persistent. For example, before a well is plugged, wells are often “idled” for a certain amount of time. The maximum length of time that a well can be idled varies from state to state, or province to province, after which wells are considered temporarily abandoned (T.A.), though terminology will vary. The initial term of the T.A. stage varies from as little as 12 months in certain states to as long as 60 months. However, many states and provinces allow the T.A. stage to be extended and even perpetuated by demonstrating that the well has “future utility.” The requirements for determination of “future utility,” however, are not applied uniformly. Ultimately, the T.A. extension process allows wells that in many cases will never be productive again to remain in that status for decades, which allows methane to continue to emit and the risk of groundwater contamination to persist long past the point that these wells could have been plugged/remediated. If regulation of the oil and gas industry becomes more stringent, there may be an increase in orphaned wells as operators are unable to meet their asset retirement obligations.

While state and provincial regulations do require that operators demonstrate financial assurance through bonds to meet well closure obligations, reports show that bonding amounts are grossly insufficient to cover plugging documented wells, leading to challenges when it comes time for operators to fulfill their retirement obligations. Proper plugging and remediation of all of the U.S. and Canada’s OOG wells is now an extremely large financial burden for local and federal governments, and there are significant backlogs because of lack of resources, equipment, and experienced personnel. Reports cite prices that range from USD 24-435 billion to plug and remediate up to 500,000 wells for the lower value and an estimate of most of the existing documented OOG wells for the upper value. And as cited earlier, the number of wells is likely to be in the millions.

How do carbon markets help address this challenge?

Carbon markets can provide financial incentives for additional action that complements state and government led initiatives. While not a silver bullet, carbon finance can provide an innovative contribution by supporting continuous improvement and increased knowledge and data, as well as promoting a long-term solution with results that are measured, monitored and verified over the course of decades.

In spite of recent U.S. federal funds being channeled toward this problem, along with existing programs to address orphaned wells in Canada, the inventory of orphaned wells will likely increase and it is unknown how many wells will become orphaned and what the associated plugging costs will be. By leveraging the carbon market to financially support the plugging of orphaned wells, it is possible to direct a significant level of capital to help address the problem, alongside other partners.

ACR’s Methodology

ACR has published a first of its kind Methodology for the Quantification, Monitoring, Reporting and Verification of Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emission Reductions from the Plugging of Orphaned Oil and Gas (OOG) Wells. The methodology, developed with the support of Dr. Mary Kang of McGill University, provides the eligibility requirements and accounting framework for the creation of carbon credits from the reduction in methane emissions by plugging OOG wells.

The ACR methodology is designed to address a clear gap in our current ambition, ability and resources to plug orphaned wells. It is intended to incentivize the plugging of leaking oil and gas wells in the U.S. and Canada, creating a pathway for carbon markets to help finance this activity and will help focus funds on higher emitting wells. We expect it will drive investment in innovation and technology, which leads to the collection of more data. Our hope is that as we better understand this issue, legislative and other solutions can be developed that will help to address the situation based on a stronger understanding of what it will take to solve it.

The potential costs for capping wells vary widely. While carbon credit purchases may be enough to cover the full costs of capping some wells, most funding will be supplemental to additional state, non-profit and federal funding for well capping. Each state has different rules and regulations that will determine whether participating in the carbon market is the right investment. For some states the contribution to bonds to cover the costs of wells may be adequate, but that isn’t guaranteed now or in the future.

Additional Benefits

Unplugged oil and gas wells impose more than climate costs. Impacts can include air pollution, groundwater contamination, soil degradation, damage to ecosystems, and risk of explosions, all of which pose threats to human health. Plugging OOG wells can mitigate these impacts, providing both short- and long-term environmental benefits.

Ozone Depleting Substances

What is the challenge?

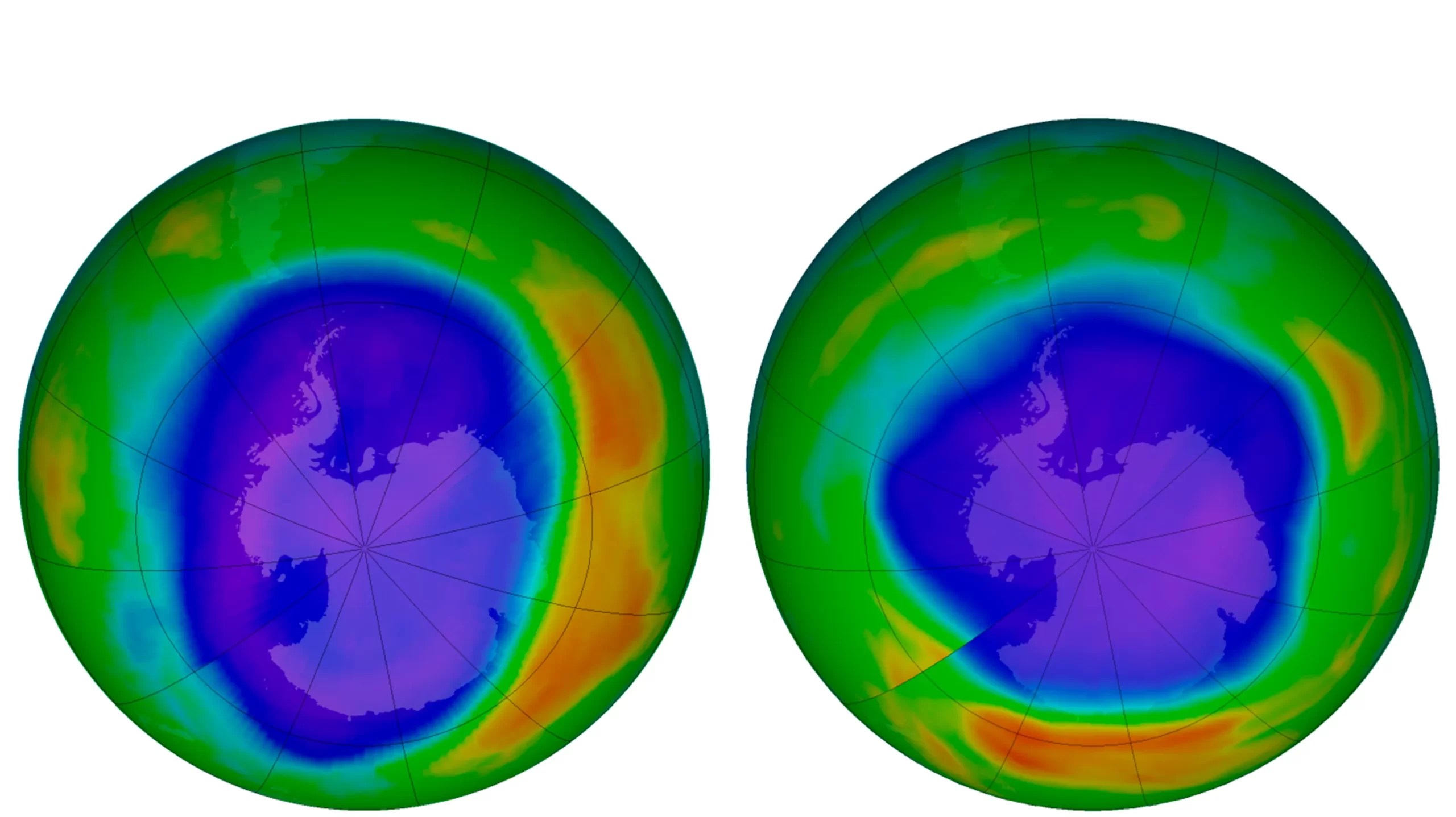

Ozone Depleting Substances (ODS) are materials like chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) that are commonly used within refrigeration and air conditioning systems, aerosol sprays, medical devices and foam blowing agents for insulation and noise reduction in buildings, appliances, coolers, marine applications and industrial pipe insulation. CFCs and HCFCs are internationally designated as ODS because they participate in chemical reactions in the atmosphere that deplete the stratospheric ozone layer.

ODS are also some of the most dangerous greenhouse gasses (GHGs) in terms of climate change, with up to ten thousand times the heat trapping properties of carbon dioxide over a 100-year period. Global Warming Potential (GWP) is a measurement to assess the global warming impacts for different gasses compared to an equal amount of carbon dioxide over a period; CFCs have 100-year GWPs of between 4,750 to 10,900.

Although the production and consumption of CFCs has been phased out by all nations and HCFCs have been phased out by most developed nations[i] under the Montreal Protocol, the use of these ODS continues, and it is common practice in many countries to continue to recycle these compounds for reuse in equipment that was originally designed to use them until the equipment is retired.

ODS refrigerants leak into the atmosphere throughout production, use and disposal. Worse still, ODS are sometimes vented during servicing or disposal of equipment, although certain countries ban this practice. As equipment reaches end of life, there is dwindling use for the remaining ODS. Because destruction is not mandated, unused supplies can be stockpiled for long periods, over which time ODS leak into the atmosphere unless destroyed.

What is the solution?

Under the Montreal Protocol, the production of CFC refrigerants within signatory countries was phased out in 2010 and since then significant progress has been achieved. The signatories have successfully phased out 98 percent of total virgin ODS compared to 1990 levels, with most developed countries planning a full phase-out of HCFCs by 2030. According to recent analysis, the ban on producing new ODS is estimated to prevent as much as 0.5 to 1 degree Celsius of extra global warming by the end of the century. Or in other words, eliminating ODS like CFCs and HCFCs could avoid as much as the equivalent of 9 billion metric tons of CO2 between 2020-2100, comparable to avoiding the emissions of nearly two billion passenger vehicles for one year.

However, despite the progress made under the Montreal Protocol, ODS still represent a significant input of GHGs into the atmosphere that can contribute to future global warming now and into the future. Destruction of ODS is a big bang for the buck, no regrets, common sense, right-now GHG mitigation strategy. ODS sitting in a stockpile is equivalent to being in the atmosphere as there is no other fate if not destroyed. The latest IPCC report, for the first time, dedicated a chapter to addressing the need to significantly remove or reduce pollutants like ODS that have a high GWP in the near-term. The report states that waiting to act on eliminating these GHG emissions will make it significantly harder for society to meet Paris Agreement targets.

How do carbon markets help address this challenge?

Absent the incentive provided by carbon markets, the only fate of any ODS that cannot be or is not recycled is to stockpile and eventually vent into the atmosphere. This is because destruction of ODS in the US and most other countries is not mandated by law and the costs to collect and destroy ODS are high. Carbon markets are essential for catalyzing climate action in the absence of regulatory requirements. The revenue generated from the sale of carbon credits from ODS destruction at current market prices can cover costs to collect and destroy ODS with high GWP like CFCs, making it profitable generating private sector interest.

However, destruction of ODS like HCFC-22, the most abundant ODS that continues to be recycled and reused, is still not attractive at current carbon prices. The destruction of ODS could be greatly accelerated if the price for carbon credits generated from destruction of ODS like HCFC-22 were to increase to the range of $30-40 a ton.

ACR’s methodology

ACR currently has two methodologies for the destruction of ODS to generate carbon credits.

The Methodology for the Quantification, Monitoring, Reporting and Verification of GHG Emission Reductions from the Destruction of Ozone Depleting Substances (ODS) and High-GWP Foam, specific to the U.S.,allows eligible CFCs and HCFCs sourced in the U.S. to be destroyed in EPA-regulated destruction facilities in the U.S. This methodology is currently being updated to add Canada as a source country, to allow the destruction in a facility approved by the Montreal Protocol’s Technology and Economic Assessment Panel (TEAP), and to expand the list of eligible ODS.

The “Methodology for the Quantification, Monitoring, Reporting and Verification of GHG Emission Reductions from the Destruction of Ozone Depleting Substances (ODS) from International Sources” allows destruction of eligible CFCs from international sources in any TEAP-compliant destruction facility in the world and EPA-permitted destruction facilities in the U.S. This methodology is also being updated to expand eligible ODS to HCFCs and other high-GWP halogenated compounds and to make eligibility and monitoring requirements more specific to different regions around the world.

These ACR methodologies provide access to carbon markets as an incentive to destroy these materials. They provide a framework for the quantification, monitoring, reporting and verification of GHG gas emission reductions associated with the sourcing and destruction of high GWP ODS sourced from stockpiles, equipment, refrigeration systems, or other supplies, including but not limited to cans, cylinders, and other containers of recovered, reclaimed or unused ODS.

Additional benefits

Diminishing supply of CFCs, and thus their increasing cost, helps to make the continued use of CFC-dependent equipment uneconomic, in addition to driving the development of non-polluting CFC replacements. The increase in use of energy efficient equipment reduces GHG emissions, as well as other pollutants, while saving money. This also accelerates transition to natural refrigerants like ammonia and carbon dioxide that are naturally present in the environment and hence provide multiple environmental benefits compared to synthetic ODS.

—

[i] Any country that is a developing country and whose annual calculated level of consumption of the controlled substances in Annex A is less than 0.3 kilograms per capita.