This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Resources Tag: PRIMER

Restoration of Pocosin Wetlands

Pocosin wetlands are unique freshwater ecosystems endemic to eastern regions of Virginia south to the panhandle of Florida (which are also the ancestral homelands of the Lumbee, Waccamaw, Coree, Manú, Tuscarora, and Muscogee Tribes, among many others1.

These wetlands occur in the middle Atlantic Coastal Plain ecoregion2 and are characterized by annual flooding and drying periods3. Peat depth in these systems can exceed several meters, and the overlying vegetation may range from evergreen shrubs (such as Cyrilla racemiflora) to pond pine (Pinus serotina)3,4. Since European settlement in the early 18th century, roughly 60% of the nearly 2.47 million acres of Pocosin wetlands that originally covered the southeastern US have been drained for agriculture, forestry operations, or other development5.

WHAT IS THE OPPORTUNITY?

Studies indicate that drained Pocosin wetlands are significant sources of carbon dioxide, due to decomposition of peat by microbial communities5. Where wetlands remain drained, they emit approximately 8.6 tons of carbon dioxide per acre per year5,6, almost twice the emissions of the average passenger vehicle7.

Worldwide, emissions from drained peatlands are responsible for approximately 4% of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, making wetland restoration a priority for climate action8. The process of rewetting Pocosin wetlands restores the function of these ecosystems, turning them from sources of greenhouse gases into net sinks5. In a Pocosin system, wetland plants grow and eventually die under naturally acidic and low-oxygen conditions. Flooding in anaerobic conditions promotes the organic material to persist and accumulate rather than being decomposed by microbes and released as carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. This process of a functioning peatland ecosystem forms the basis for restoration projects using the ACR methodology.

HOW CAN CARBON MARKETS HELP UNLOCK OPPORTUNITY?

Carbon projects that focus on the restoration of Pocosin wetlands reestablish the natural cycles of periodic flooding and drying through the removal of drainage ditches and other structures that prevent such conditions. The straightforward act of rewetting (flooding) these systems alters the microbial community, drastically reduces microbial respiration, and eventually

restores the Pocosin wetland’s function as a sink for greenhouse gases. One analysis of land use across four states in the southeastern US indicates that more than 300,000 acres of drained wetlands could be restored through rewetting, thus reducing emissions by as much as 1.6 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent per year5.

ACR’s Restoration of Pocosin Wetlands methodology provides a framework to quantify the emission reductions and removals associated with restoring Pocosin sites to their natural conditions. For every verified ton of GHG emission reductions and removals due to the project activity, ACR issues a serialized carbon credit, also known as an Emission Reduction Ton (ERT). ERTs issued to the project can then be bought and sold in the carbon market.

ACR’S METHODOLOGY & CORE PRINCIPLES

Like all of ACR’s methodologies, the Pocosins Restoration methodology operates in conjunction with the ACR Standard, which reinforces the integrity of all ACR’s project types through the application of ACR’s core principles. These include:

- Real: Emission reductions or removals have been verified to have occurred (ex-post).

- Additional: Emission reductions or removals are beyond what would have occurred in the absence of the project activity and under a business-as-usual (baseline) scenario. Pocosin projects demonstrate additionality by applying the ACR three-pronged test:

- Project activities must exceed current effective and enforced laws and regulations, and activities must not be required by any law or regulation.

- Project activities must exceed common practice when compared to similar landowners in the geographic region.

- Project activities must face a financial or implementation barrier.

- Permanent: Emission reductions or removals are permanent, or there are binding measures to mitigate and compensate for reversals.

- Net of Leakage: Emission reductions or removals take into account any increase in emissions outside the project boundary due to activities taken by the project. For Pocosin wetland restoration projects, potential leakage is mitigated by Methodology applicability conditions and therefore is not included in stock calculations.

- Independently Verified: Emission reductions or removals are validated and verified by a qualified, accredited, and independent third party.

- Transparent: The ACR website and registry provide publicly available information on the methodology, the projects, and credits.

BASELINE AND PROJECT DEVELOPMENT

The baseline scenario under the methodology assumes the continuation of a drained wetland state (where the water table is 30 – 60 cm below the surface5) and continued emissions from the degradation of peat. The methodology centers on two different approaches for estimating belowground emissions: (1) a stock change approach which estimates emissions from net surface level change (due to subsidence and root dynamics), and (2) a flux approach which models emissions as a function of one or more proxy variables (e.g., soil moisture, temperature, etc.) that are demonstrated to be significantly correlated with belowground emissions, as demonstrated by Richardson, et al (2022, 2023)5,9.

Monitoring is conducted in the project area, as well as in a valid baseline site that matches conditions expected in the project area in the absence of the project activity (i.e., rewetting). Carbon credits are issued based on the difference in accrued carbon between the project and baseline scenarios.

Either net surface elevation change (stock change approach) or one or more proxy variables (flux approach) are monitored to estimate emissions from belowground. Trees and woody shrubs are monitored on permanent sample plots to assess and account for any detected differences in stock change due to differential growth, recruitment, or mortality between the project area and the baseline site. With the stock change approach, peat accretion is monitored via net surface elevation change (a proxy measurement for peat accumulation). Peat accretion is not monitored with the flux approach.

Crediting is a function of the difference between project scenario (rewetting) and baseline (drained) carbon stocks.

ADDITIONAL BENEFITS

Rewetting previously drained Pocosin wetlands offers both climate and other benefits, such as improved water quality, restored wildlife habitat and flood mitigation. ACR utilizes the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a metric for tracking a project’s SDG Contributions. Tracking SDGs is one of several project requirements outlined in the GHG Project Plan – an overarching document that ensures adherence to the ACR standard and methodology. Some of the benefits from Pocosin projects, as defined by the SDGs, include:

- GOAL 6: Clean Water and Sanitation

- GOAL 13: Climate Action

- GOAL 15: Life on Land

SOURCES

- Native Land Digital. (2024). Native-Land.ca | Our home on native land. 2024

- Ecological Regions of North America; Level I-III. North American Atlas. (2006). Commission for Environmental Cooperation. Montreal, QB. NA_CEC_eco3_v10.1_GGfnl (epa.gov).

- Walbridge, M. R., & Richardson, C. J. (1991). Water quality of pocosins and associated wetlands of the Carolina Coastal Plain. Wetlands, 11, 417-439

- Richardson, C. J. (1991). Pocosins: an ecological perspective. Wetlands, 11, 335-354.

- Richardson, C. J., Flanagan, N. E., Wang, H., & Ho, M. (2022). Annual carbon sequestration and loss rates under altered hydrology and fire regimes in southeastern USA pocosin peatlands. Global Change Biology, 28(21), 6370-6384.

- Joosten, H., Sirin, A., Couwenberg, J., Laine, J., & Smith, P. (2016). The role of peatlands in climate regulation (Vol. 66). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. (2023) Greenhouse Gas Emissions from a Typical Passenger Vehicle.

- https://www.ramsar.org/sites/default/files/documents/library/rpb5_restoring_drained_peatlands_e.pdf

- Richardson, C. J., Flanagan, N. E., & Ho, M. (2023). The effects of hydrologic restoration on carbon budgets and GHG fluxes in southeastern US coastal shrub bogs. Ecological Engineering, 194, 107011

Active Conservation and Sustainable Management on U.S. Forestlands

U.S. FORESTS ARE LOST EVERY YEAR

Every year, the United States loses more than three million acres (1.2 million hectares) of forestland to other land uses, such as real estate development, agriculture or mining. The highest rates of forest loss tend to be around fast-growing suburban areas, as well as in areas of agricultural expansion. Nearly 40% of forestland in the US is owned by families and individuals. When the financial value of a forest is significantly less than the value an owner could achieve from other land uses, there is a risk of forest conversion.

As forestland is converted to other land uses, previously stored carbon is emitted into the atmosphere. Globally, deforestation and forest degradation contribute 12-20% of greenhouse gas emissions.

In the United States, forests comprise the largest carbon sink, capturing and storing 13% of the nation’s annual greenhouse gas emissions. Nonetheless, forest loss continues to represent a substantial source of U.S. carbon emissions, counteracting approximately 20% of the gross carbon sequestered by annual forest growth. Forest loss also negatively impacts biodiversity, drinking water, recreation, and cultural values.

Forests are critical to achieve the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement. One key strategy is to prevent the conversion of forests to other land uses.

CARBON MARKETS CAN INCENTIVIZE FOREST CONSERVATION

The fate of a forested parcel often comes down to a financial decision. Carbon markets have emerged as an important tool to conserve forests by creating a financial incentive for standing forests. Like traditional forestry, in which management is focused on maximizing returns from timber output, forestlands can now be managed for maximizing returns from carbon sequestration.

By creating a salable and tradable market instrument – a carbon credit – for the climate benefits of active forest conservation, carbon markets offer landowners a new opportunity to sustainably manage their forests.

A RIGOROUS METHODOLOGY GENERATES HIGH-INTEGRITY CREDITS

The Methodology for the Quantification, Monitoring, Reporting and Verification of Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions from Active Conservation and Sustainable Management on U.S. Forestlands describes the “rules” for generating carbon credits by conserving forests.

To be eligible, a carbon project must first demonstrate the credible threat of conversion to an eligible alternate land use, which includes agriculture, residential, commercial or recreational development, or mining. A project-specific “highest and best use” of the land if it were converted to another use underpins the baseline, an alternate scenario that is demonstrably the most profitable scenario that could occur in the absence of the project.

Through a qualified appraisal, the alternate land use must be shown to be significantly more profitable – at least 50% more – than the forested land use. The alternate land use must also be operationally feasible based on the landscape, infrastructure, and market demand.

Projects forgo conversion to the highest and best use for at least 40 years by enacting a legally binding conservation easement that ensures long-term carbon storage and accumulation associated with continued forest cover. This is a long-term solution with results that are measured, monitored, and verified over the course of decades.

FORESTS PROVIDE AN ARRAY OF BENEFITS

Life on Earth depends on forests. From the water we drink to the air we breathe, forests have much more value than timber alone. However, the ecosystem services forests provide have long been undervalued. Carbon markets offer a way to financially value the climate mitigation potential of forests, along with the suite of other ecosystem services, such as clean water and biodiversity.

Emerging markets for other ecosystem services could be paired with carbon projects to provide additional revenue streams that further incentivize forest conservation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Active Conservation and Sustainable Management on U.S. Forestlands methodology was developed by Green Assets in conjunction with ACR; it is dedicated to the memory of D. Hunter Parks (1976 – 2022), Green Assets founder. Hunter’s lifelong passion for conservation, his inspiration and insight, and years of experience in helping pioneer the forest carbon market enabled the creation of this methodology. May his legacy of conservation live on through the unique natural places that are conserved each time an active conservation and sustainable management project is developed.

Afforestation and Reforestation of Degraded Lands

What is the opportunity?

Establishing forests on marginal and degraded lands presents one of our greatest opportunities to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and mitigate climate change.

Approximately 130 million acres in the continental U.S. are suitable for afforestation and reforestation (A/R) activities[1]. Expanding A/R on these lands has the potential to capture and store more than 314 million tons of CO2 annually (equivalent to annual passenger vehicle emissions of ~ 67 million cars or ~15% of the U.S. Paris Agreement climate target[2],[3].

Restoring forests also provides many non-carbon ecosystem benefits, such as biodiversity, habitat, water quality, and soil health.

Marginal site conditions, land use conversion, previous intensive management, and/or natural disturbance (e.g., wildfire, pests, pathogens) are all reasons forests may not naturally occur or may not naturally regenerate. In these cases, A/R efforts such as site preparation and planting are necessary to establish forests on these lands.

How can carbon markets help unlock the opportunity?

Abundant A/R opportunities exist across all U.S. states and for all different types of forest landowners. However, the upfront costs associated with A/R initiatives are often significant, making it difficult to raise the financial and human capital necessary to implement reforestation at scale and over the long timeframes needed to realize and ensure impact. A/R carbon projects offer an additional revenue stream for landowners that helps to incentivize project development and recoup associated expenditures.

A/R carbon projects create enabling conditions through site preparation, and/or plant trees where natural forest has been displaced or does not naturally occur. As the trees grow, they sequester carbon.

Carbon projects generate revenue by quantifying and monetizing the verified carbon sequestration benefit of planting new forests. Each carbon credit issued represents a ton of CO2 removed from the atmosphere (and therefore is classified as a “removal” credit), which can then be monetized in the carbon market.

The voluntary carbon market has recently seen unprecedented growth and demand for carbon credits, stemming from over 2,000 corporations pledging to reduce and offset their GHG emissions to achieve net zero targets. As part of this surge in corporate net zero commitments, a new demand for verified ‘removal’ credits (credits attributed to carbon sequestration from tree growth, as opposed to reduced or avoided emissions) has emerged in recent years[4].

ACR’s methodology

ACR’s Methodology for Afforestation and Reforestation of Degraded Lands is built on core principles that ensure the highest environmental integrity and scientific rigor. It applies to lands that are degraded and are expected to remain degraded in the absence of the project. A/R projects in non-REDD+ countries are eligible for crediting.

The methodology establishes guidelines for identifying degraded land, determining the eligibility, and quantifying the carbon stocks in tree biomass associated with the project activity – ex-post. Carbon in wood products, litter, and soil organic carbon are optionally quantified.

A/R projects often occur on lands previously converted to agriculture or livestock, lands that have been abandoned, or those that are producing marginal yields. Only native species that would occur under natural forest conditions are acceptable for planting.

A/R credits developed under this methodology qualify for a first of kind feature in the ACR registry[5] to be tagged as “removals”. Removals are quantified, verified, issued, labeled, and therefore may be specifically marketed as such.

Baseline and Project Scenario Development

The baseline and project scenario under the methodology assume initial carbon stocking to be negligible (i.e., the land would not return to forest cover without human intervention). This assumption stems from the eligibly requirements of the methodology which require the project be implemented on degraded land that is expected to continue to degrade in the absence of the project.

Where trees are completely absent across the site and regeneration is not expected, the baseline will be zero. Where some natural regeneration occurs, remnant trees are either excluded from the project area or considered in both the project and baseline scenarios. Regeneration monitoring areas are used to monitor naturally occurring regeneration on proxy sites outside the project area to ‘net’ out any natural regeneration and serve as an additionality safeguard.

Crediting is a function of the difference between project scenario (tree planting) and baseline (non-forest) carbon stocks.

The graph below provides a generic example of the different trajectories for baseline and project carbon stocks. The example illustrates a project with seedlings planted across 10,000 acres and monitored over a 40-year crediting period. The growth of trees above the zero baseline indicates the volume of removal credits issued to the project as they are verified ex-post over time.

ACR Core Principles

ACR’s methodologies are built from the carbon market’s founding core principles. These principles include:

Real: The emission reductions or removals must be measured, monitored, reported, and verified ex-post to have already occurred.

Additional: The project must generate ‘additional’ GHG removals, that exceed what would have occurred under a business-as-usual (baseline) forest management scenario.

A/R projects demonstrate additionality by applying the ACR three-pronged test:

- Project activities must exceed current effective and enforced laws and regulations, and activities must not be required by any law or regulation.

- Project activities must exceed common practice when compared to similar landowners in the geographic region.

- Project activities must face a financial or implementation barrier.

In addition, ACR requires the use of the tool “Combined tool to identify the baseline scenario and demonstrate additionality in A/R CDM project activities.”

Permanent: Projects must commit to long term monitoring, reporting, and verification of carbon stocks for a minimum of 40 years and must contribute to a reversal risk buffer pool at each issuance to compensate for unintentional reversals. Requirements for reversal mitigation are set out in the legally-binding ACR Reversal Mitigation Agreement and include project compensation for intentional and unintentional reversals.

Free of Leakage: For A/R projects, leakage is defined as the displacement of agricultural activities resulting in a decrease of removals or increase of emissions to areas outside the project boundary. Leakage is conservatively estimated and deducted at each credit issuance to account for any potential displacement of agricultural production to lands outside the project area.

Verified: All projects must be validated and verified by a qualified, accredited, and independent third party to assess the project against ACR requirements and that they have correctly quantified net GHG reductions or removals.

Transparent: All relevant documents and credit issuances are publicly available. ACR requirements and processes are clearly outlined in the ACR Standard and approved methodologies.

Additional Benefits

Reestablishing forest cover offers both climate and co-benefits. ACR utilizes the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)[6] as a metric for tracking a projects SDG accomplishments. Tracking SDGs is one of several project requirements outlined in the GHG Project Plan – an overarching document that ensures adherence to the ACR standard and methodology.

Some of the benefits from A/R projects, as defined by the SDGs, include:

- GOAL 6: Clean Water and Sanitation

- GOAL 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

- GOAL 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure

- GOAL 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

- GOAL 13: Climate Action

- GOAL 15: Life on Land

Contact ACR

For more information or questions on A/R carbon projects, please contact the ACR forestry team at ACRForestry@winrock.org

[1] https://www.americanforests.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Ramping-Up-Reforestation_FINAL.pdf [2] Cook-Patton et al. 2020. Lower cost and more feasible options to restore forest cover in the contiguous United States for climate mitigation. One Earth 3, 739-752. [3] Forgione et al. 2018. Natural climate solutions for the United States. Science Advances 4(11), eaat1869. [4] Forest Trends’ Ecosystem Marketplace. 2021. ‘Market in Motion’, State of Voluntary Carbon Markets 2021, Installment 1. Washington DC: Forest Trends Association. [5] https://americancarbonregistry.org/news-events/news/acr-launches-innovative-registry-infrastructure-for-removal-credits [6] https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/news/communications-material/

HFC Refrigerants

What is the challenge?

A common substitute for Ozone Depleting Substances (ODS) controlled under the Montreal Protocol, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) are greenhouse gasses (GHGs) used in a wide variety of applications, including refrigeration and air-conditioning systems. HFCs are a major climate concern because of their high global warming potential (GWP). GWP is a measure of how much energy 1 ton of a gas, once emitted into the atmosphere, will absorb radiation over a given period of time, relative to the emissions of 1 ton of carbon dioxide.

HFCs, when released into the atmosphere, have 100-year GWPs that can exceed ten thousand. Even small amounts of these super heat-trapping gasses can have a significant warming impact on the atmosphere. Currently, HFCs account for around 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions and as much as 3% in many developed countries. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), in 2020, almost half of the 376 million metric tons of GHG emissions from industrial processes in the US came from ODS substitutes, primarily HFCs. Left unchecked, HFCs could account for up to nearly 20% of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide by 2050.

HFCs enter the atmosphere through the production, use and disposal of a multitude of appliances and applications vital to modern life. These include the refrigeration units keeping our food and medicine safe and the air conditioning units we need to keep buildings habitable.

The irony is, as climate change worsens and we experience warmer temperatures, the more we will rely on these kinds of appliances.

What is the solution?

When it comes to refrigeration, refrigerants with much lower GWPs exist – some representing more than a 1,000% reduction from what is currently used in refrigerated appliances. At least ten states including California and Washington have introduced regulations to limit use of high-GWP HFCs.

In September 2021, the EPA established a new rule to reduce the use and production of HFCs by 85% over the next 15 years. While the rule is a welcome and necessary step in preventing further warming, the phase-out timeline still leaves an open window for HFCs to continue to be used and produced in the years ahead when we are facing an urgent need to rapidly accelerate our climate ambition to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement.

How do carbon markets help unlock the solution?

While regulation will certainly begin a shift to lower-emitting alternatives, on its own, it won’t require or spur the rapid transition to ultra-low GWP (i.e. < 15) alternative refrigerants we truly need. Long-lived equipment using HFC refrigerants with high GWP will continue to be produced and used in our grocery stores and homes for well over a decade. So, while the regulations are welcome, we’re leaving a lot of climate action on the table in the short term.

The ability to generate carbon credits can incentivize manufacturers to quickly start producing appliances that utilize ultra-low GWP refrigerants, support current producers of these refrigerants, and reduce costs for industries that use this equipment to procure sustainable options long before they would be required to do so by regulation or the natural end-of-life of existing products. The carbon credits can also help lower the cost to transition to low-GWP or even natural refrigerants like ammonia and carbon dioxide. Industry estimates show that complete transition to natural refrigerants can cost existing grocery stores upwards of a million dollars per store.

By providing financial incentives to manufacturers to rapidly transition to ultra-low GWP refrigerants, carbon credits can prevent a significant number of near-term emissions from HFCs, making an important contribution to climate action.

ACR’s methodology

ACR has published version 3.0 of the Methodology for the Quantification, Monitoring, Reporting and Verification of Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions and Removals from Advanced Refrigeration Systems.

The intent of the Methodology is to incentivize GHG emission reductions through the deployment and use of advanced refrigeration systems in large commercial and stand-alone commercial refrigeration.

This methodology allows for the generation of carbon credits by manufacturers of stand-alone refrigeration equipment that use refrigerants with GWPs under 15 –and supermarkets and groceries that install new refrigeration equipment with low-GWP refrigerants or switch to approved refrigerants under the EPA’s Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP) program in existing refrigeration equipment.

ACR has also published updates to its Methodology for the Quantification, Monitoring, Reporting and Verification of Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions from Certified Reclaimed HFC Refrigerants, Propellants and Fire Suppressants, Version 2.0. This methodology incentivizes use of certified reclaimed HFCs over virgin HFCs. Use of reclaimed HFCs will prevent all GHG emissions associated with virgin HFCs. According to the EPA, in 2020, only 2% of the HFCs available for use in the US came from reclaimed HFCs. This shows that there is still a significant opportunity for additional climate action by incentivizing the use of reclaimed HFCs.

Additional benefits

HFCs are not only high-GWP GHGs, but also short lived climate pollutants. GWP is a relative term that represents absolute GWP of a GHG relative to the absolute GWP of carbon dioxide, which is the reference GHG. GWP is normally estimated for a period of 100 years because it takes 100 years for 70% of the carbon dioxide to disintegrate in the atmosphere. However, in case of short-lived climate pollutants, like some HFCs, 80% disintegration occurs within 20 years. So, HFCs heat the atmosphere at a much higher rate in the first 20 years, several times higher than their 100-year GWP values. Moving away from use of high-GWP HFCs and using reclaimed HFCs provides additional benefit over GHGs like carbon dioxide by avoiding rapid warming of the planet in the short term.

Switching from HFCs to low-GWP natural refrigerants like ammonia and carbon dioxide that are renewable and naturally available in the environment also provides many additional environmental benefits compared to manufacturing synthetic HFC refrigerants.

Methane Emissions from Landfills

What is the challenge?

There are more than 2,000 active landfills in the U.S. When organic material in these landfills decomposes without oxygen it generates both carbon dioxide and methane, a potent greenhouse gas that has 28 times the warming power of CO2 over 100 years and 84 times the warming power over the first 20 years after it reaches the atmosphere.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that landfills are the third-largest source of human-related methane emissions in the United States, accounting for 15.1% of these emissions in 2019, equivalent to the annual emissions from more than 21 million passenger vehicles. Regulations under the Clean Air Act require landfills of a certain size to install and operate a methane gas collection and control system.

Currently, these systems are manually operated through a process known as well-field tuning. Once a month, a technician is required to measure the gas composition, flow, temperature, and pressure at each collection point at a landfill, and to make adjustments to reduce the methane emissions being leaked into the atmosphere.

Although standard gas collection systems are better than nothing, they still allow significant amounts of methane to leak into the atmosphere. Manual well field tuning is not optimized for methane gas collection even if it does a good job of reducing other landfill gasses. Even modest improvements in collection efficiency can have significant impacts at scale.

What is the solution?

The good news is that technology exists that can automate the well field tuning process, thereby increasing methane collection efficiency. Rather than monthly adjustments, cellular connected sensor systems can take hourly measurements and use cloud-based computing to automatically make small valve adjustments to continuously reduce the emissions of methane and other gasses and optimize the collection process.

For a typical landfill where this gas collection system technology is used, it is estimated that 50,000 tons CO2 equivalent per year of emission reductions can be achieved by capturing methane in addition to what would be captured with a standard system. Applied at the thousand largest landfills in the country, this could produce emissions reductions of 50 million tons a year of CO2 equivalent.

How can carbon markets help unlock the solution?

There are significant costs associated with the installation and operation of these automated collection systems. Carbon markets can play an important role in the industry by promoting action that goes above and beyond existing regulations and creating a financial incentive for landfills to install automated systems that would not be economical otherwise. Landfills can use the revenue generated from the sale of high-quality carbon credits to recoup the costs of installation and to benefit from enhanced gas collection moving forward.

ACR’s methodology

ACR’s published Methodology for the Quantification Monitoring, Reporting and Verification of Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions and Removals from Landfill Gas Destruction and Beneficial Use Projects (v2.0) has the potential to accelerate the adoption of Automated Landfill Gas Control Technology for a large number of landfills due to the opportunity to generate carbon finance from the sale of carbon credits.

Until this methodology was released in 2021, carbon credits could not be generated on landfills that are required by regulations to install and operate gas collection and control systems. As a result, some of the largest landfills in the U.S. were not eligible to participate in carbon markets.

The ACR methodology creates an avenue for crediting for landfills that go beyond regulatory requirements with advanced technologies and more efficient capturing.

Additional benefits

Automated technology reduces the amount of time landfill personnel have to spend in the landfill itself, which is often a dangerous environment to work in; it reduces odors associated with non-methane emissions; and it also reduces non-Methane organic compound emissions, which have adverse effects on human health and air quality. Many large urban landfills are also in proximity to communities that have the lowest income, lowest value housing, and often have a high density of underserved and under-represented populations, who benefit from the reduced odors and air quality improvements.

The additional methane will also increase availability of renewable fuel for both thermal applications and electricity generation.

Foam Blowing Agents

What is the challenge?

Foam products are manufactured using blowing agents that produce a chemical reaction to form a hardened cellular structure. These blowing agents are used in a variety of manufacturing applications, including insulation, marine buoyancy, ventilation and refrigeration.

Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which are often used in foam blowing agents, are extremely potent greenhouse gasses (GHGs). HFCs were developed in the 1990s to replace ozone depleting substances (ODS) like chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). In recent years, however, scientists discovered that most HFCs have extremely high global warming potential (GWP) – trapping thousands of times more heat than carbon dioxide.

Foam blowing agents are emitted into the atmosphere during manufacturing, use and, largely, at the end of life when they are discarded. Since it is difficult and expensive to extract blowing agents from foam at the end of life for reuse or destruction, 100% of foam blowing agents eventually get emitted into the atmosphere during the foam lifecycle.

Independent industry research data shows that more than 80% of foam blowing agents in use today are still high-GWP compounds. Since these blowing agents will eventually leak into the atmosphere, it is very important to switch to low-GWP alternatives.

What is the solution?

Experts still agree that the use of foam blowing agents, in general, is important for efforts to improve energy efficiency in the utility sector. For example, blowing agents are often used for commercial and residential insulation, and estimates suggest that improved insulation in the residential building sector could lower total home energy costs by an average of 11 percent.

However, to reduce climate impact, manufacturers must transition away from HFC-based foam blowing agents and adopt alternatives with much lower GWP. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) currently has a list of accepted alternatives for foam blowing agents under its Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP) program.

These alternatives are determined by reviewing a variety of characteristics, including each proposed substitute’s ozone depletion potential, flammability, toxicity, GWP, and occupation and consumer health and safety.

How can carbon markets help unlock the solution?

There is industry interest in adopting foam blowing agents that do not deplete the ozone and have low GWPs. Nevertheless, many manufacturers have not adopted low GWP blowing agents due to technical and financial barriers that currently make HFC-based blowing agents more economically attractive. Independent industry research data shows low-GWP blowing agents – such as hydrofluoroolefin (HFO) – are around 3 times more expensive than HFCs. This is further exacerbated by the ongoing global supply shortages of HFOs that has led many manufacturers to cut down production of low GWP foams.

Finance from the sale of carbon credits can help break through these barriers. Credits are determined by the emissions avoided through the integration of low-GWP blowing agents into the manufacturing process. The revenue from these credits is then used as leverage to cover upfront capital costs for manufacturers looking to transition away from traditional HFC-based blowing agents.

ACR’s methodology

ACR’s approved Methodology for the Quantification, Monitoring, Reporting and Verification of Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emission Reductions from the Transition to Advanced Formulation Blowing Agents in Foam Manufacturing and Use 3.0 is an important tool to catalyze support for the manufacturing industry’s transition away from high-GWP foam blowing agents.

The methodology defines the eligible blowing agents that contribute less to GHG emissions, and it incorporates data demonstrating the low market penetration rates of the eligible blowing agents to date. Since all blowing agents in foam products are eventually emitted, the methodology allows crediting for 100% of the low-GWP blowing agent used to manufacture foam.

Each project is required to include a monitoring, reporting and verification plan that meets the ACR Standard. This includes documentation of the baseline blowing agent used and records quantifying the amount of the eligible blowing agent used during the project’s timeline. The GWP for baseline blowing agent is lower for states that restrict use of high GWP blowing agents.

Additional benefits

Once manufacturers overcome the initial capital costs associated with transitioning to alternative foam blowing agents, they can likely expect improved performance and efficiency.

Among the benefits noted by manufacturers that have made the transition are a lower volume of blowing agents required to produce the foam, lower flammability, and lower toxicity compared to HFC-based blowing agents.

Carbon Capture & Storage

What is the challenge?

Global economy-wide decarbonization is required to meet the Paris Agreement target of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees by mid-century. Different sectors of the economy have vastly different exposure to this global transition to net-zero emissions. What a net zero transition entails for a technology company, for example, is very different to what it means for a natural gas power plant or cement manufacturer that have ‘hard to abate’ emissions and for which the transition to zero emissions may not be nearly so straightforward. GHG emissions are embedded in their processes, viable alternatives may not yet exist or may take time to implement, and abatement is often cost prohibitive. Hard to abate sectors include buildings and transportation (automobiles, aviation and maritime shipping) and essential industrial sectors – such as chemicals, steel and fertilizer production – which often require high heat for their processes and for which there are currently few alternatives for the direct use of fossil fuels.

The energy sector is another such hard to abate sector. While deep decarbonization and a rapid transition to renewable energy sources is critical to global climate action, there are realities that will impose certain limitations on the pace of this transition. For example, even as countries shift to renewable energy sources, due to existing infrastructure, many emissions from the energy sector are already locked-in for the next few decades. In regions like Europe and China, existing commitments and increasing energy demand in financial capital and construction demonstrate that fossil-fuel generated power plants will continue to play an outsized role in the sector between now and 2050.

What is the solution?

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) provides a technology-based solution to address industrial carbon emissions that are currently challenging or cost prohibitive to abate.

The CCS process works by capturing carbon dioxide produced in concentrated waste streams at industrial facilities and fossil fuel-generated power plants. The captured carbon is then transported and injected into secure, deep underground geological formations. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that a power plant equipped with CCS can reduce carbon emissions to the atmosphere by at least 80 to 90 percent compared to a plant without CCS. CCS equipped power plants can also supply flexible low-carbon electricity.

Additional approaches, Direct Air Capture (DAC), Bioenergy with CCS (BECCS), Biomass with Carbon Removal and Storage (BiCRS) can support the acceleration of net carbon removal. Rather than being linked to an industrial point source of carbon, DAC captures carbon dioxide directly from the air. This technological advantage allows DAC facilities to be co-located with storage reservoirs, which could reduce the cost of transporting captured carbon to storage locations and allow accessibility to low carbon energy sources to power the equipment.

BECCS is a process by which emissions from bioenergy, which are created by burning biomass, are reduced through carbon removal and storage. BiCRS captures CO2 from biomass combustion or other concentrated carbon removed from the atmosphere by biomass and combines this with carbon capture technology and geologic storage. This suite of technologies offers opportunities for negative carbon emissions when using sustainable biomass. Sustainable biomass is defined in our methodology (below) as being derived from forestry, agricultural, or municipal waste or as an energy crop cultivated on marginal or degraded land. Biomass that contributes to an increase in food prices by displacing food crops is not eligible.

Research from both the IPCC and the International Energy Agency (IEA) has shown that CCS is a critical tool to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. According to the IPCC, all pathways that limit global warming to 1.5C project the use of carbon dioxide removal in addition to emissions reduction policies. It presents three scenarios for achieving this goal that involve major use of CCS. The scenario that does not utilize CCS requires the most immediate and dramatic shift in human behavior. The role of CCS implicit in the IPCC report is somewhere between 350 and 1200 gigatonnes of CO2 that needs to be captured and stored this century.

In 2020, 26 global CCS facilities supported the capture of 40 million tons of carbon dioxide. Estimates suggest that to meet the UN’s target, CCS capacity will need to increase from its current levels of around 40 million tonnes per annum (Mtpa) to over 5,600 Mtpa by 2050. To facilitate this exponential growth, the industry will require between $655 billion and nearly $1.3 trillion in capital investment.

ACR’s methodology

ACR’s methodology for the Quantification, Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reductions and Removals from Carbon Capture and Storage Projects v2.0 – will support an expanded variety of CCS projects. As private companies continue to signal strong interest in technology-based solutions, this methodology will provide a framework for both project developers and carbon market buyers interested in high quality CCS emission reductions and removals towards their climate targets.

The methodology outlines the requirements for the creation of carbon credits by CCS project developers including eligibility, ownership, regulatory compliance and rigorous monitoring, reporting, and verification during active project operation as well as post-project to ensure permanent carbon storage.

Eligible carbon dioxide sources include power plants that burn biomass, coal, natural gas, or oil and industrial facilities such as petroleum refineries, oil and gas production facilities, iron and steel mills, cement plants, fertilizer plants, ethanol distilleries and chemical plants. The methodology will also expand point source CO2 eligibility to direct air capture and storage options to include saline formations and depleted oil and gas reservoirs.

Additional benefits

Carbon finance will also catalyze job growth in the industry, creating opportunities for workers in the fossil fuel industry to transition to high value positions. Estimates suggest that investments in the installation and construction of carbon capture facilities could create up to 64,000 jobs within the next 15 years, and an additional 43,000 jobs could be generated for maintenance and operations.

Improved Forest Management

Growth in the Voluntary Carbon Market

The voluntary carbon market (VCM) has seen unprecedented growth and demand for offset credits in recent years. The increase in demand stems from over 2,000 corporations pledging to reduce and offset their GHG emissions to achieve net zero targets. Additional demand for ACR credits is likely to emerge from the ICAO market in 2024, and from Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

To achieve net zero and transition to a carbon neutral economy, science and government leaders concede that Natural Climate Solutions (NCS) will play an essential role and can contribute up to a third of the GHG mitigation needed by scaling up forest conservation and improved land-use practices.

Improved Forest Management

Improved Forest Management (IFM) under ACR is an activity that involves forest management practices that increase on-site stocking levels beyond a business-as-usual scenario. ACR IFM projects have a crediting period of 20 years (which can be renewed), and a minimum project term of 40 years.

Project Development Processs

There are several steps that must be taken to develop and implement a successful IFM project under ACR:

Feasibility Assessment

- Non-Federal U.S. forestland that can legally be harvested

- Clear land title or timber rights

- Forest certification (if lands are subject to commercial harvest)

- Native species composition

ACR Account

- Open an account with the American Carbon Registry, sign the ACR Terms of Use Agreement

Project Development and Implementation

- Conduct forest carbon inventory

- Prepare required project documentation (i.e., listing document, GHG Plan, quantification files)

- Model a baseline scenario

- Quantify the GHG emissions reductions and removals based on project activity

- Submit monitoring reports (at least every 5 years)

- Continually update inventory (at least every 10 years)

Project Validation/Verification

- Select an ACR approved third party validation and verification body

- Validate the project within three years of the start date

- Verify required project documentation and plot based inventories (5 year minimum)

ACR Review and Credit Issuance

- Submit all verification documentation to ACR for a final internal review

- Sign the ACR Reversal Risk Mitigation Agreement

- ACR issues serialized offset credits to the project proponent on the registry

Transaction

- Offset credits are available for transaction (i.e., transfer, retirement, cancelation)

IFM Baseline and Project Scenarios

The IFM baseline is a project-specific harvesting scenario reflecting ownership, constraints, substantiated forest management practices, and financial analysis. The resulting harvest levels are used to establish baseline stocking over the crediting period.

Increased stocking in the with-project scenario is measured and compared to the established baseline. The difference between baseline and project stocking indicates a projects GHG performance, a measure of the emissions reductions or removal enhancements quantified in metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (t CO2e).

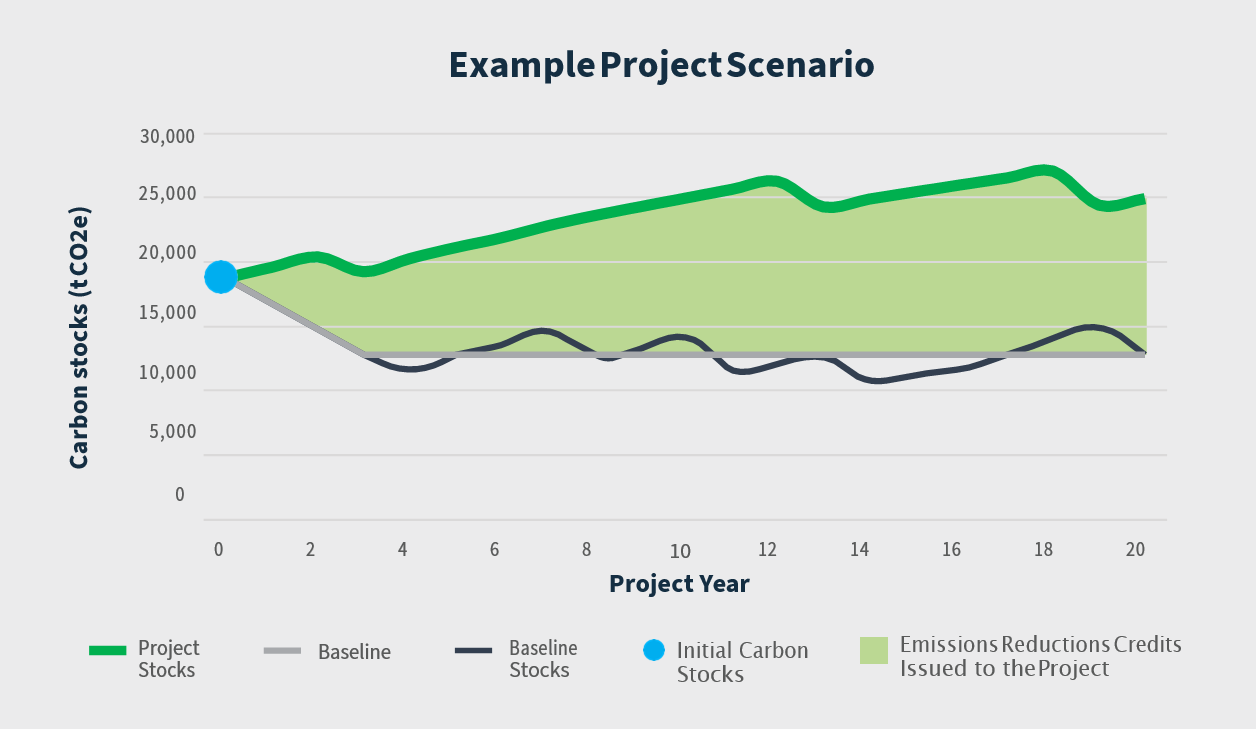

The graph below provides a generic example of different trajectories for baseline and project carbon stocks. The example illustrates a project with light harvest on 100 acres over a 20-year crediting period. The delta between baseline and project stocks indicates the volume of offset credits issued to the project.

ACR IFM Methodology and Core Principles

Carbon offsets must adhere to core principles that ensure environmental integrity and scientific rigor. These principles are the foundation of the ACR standard and IFM methodology. These core principles include:

Real: The emission reductions or removals must be measured, monitored, reported, and verified ex-post to have already occurred.

Additionality: The project must generate ‘additional’ GHG removals, that exceed what would have occurred under a business-as-usual (baseline) forest management scenario.

IFM projects demonstrate additionality by applying the ACR three-pronged test:

- Project activities must exceed current effective and enforced laws and regulations, and activities must not be required by any law or regulation.

- Project activities must exceed common practice when compared to similar landowners in the geographic region.

- Project activities must face a financial or implementation barrier.

Permanent: Projects must commit to long term monitoring, reporting, and verification of carbon stocks and must contribute to a reversal risk buffer pool at each issuance to compensate for unintentional reversals. Requirements for reversal mitigation are set out in the legally-binding ACR Reversal Mitigation Agreement and include project compensation for intentional and unintentional reversals.

Leakage: All lands under the projects ownership and/or management must be certified by a sustainable forestry certification system to safeguard against shifting harvests to other lands owned by the project proponent but not enrolled in the carbon market. A conservative crediting deduction is applied to account for the possibility that reduced harvest activities increase market demand and shift harvests to other landowners.

Verification: All projects must be validated and verified by a qualified, accredited, and independent third party to assess the project against ACR requirements and that they have correctly quantified net GHG reductions or removals.

Transparent: All relevant documents and credit issuances are publicly available. ACR requirements and processes are clearly outlined in the ACR Standard and approved methodologies.

Contact ACR

For more information or questions on how to enroll your forestlands in an IFM carbon project, please contact the ACR forestry team at ACRForestry@winrock.org.