This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines Enhance Precision in IFM

By: Kurt Krapfl

Improved forest management (IFM) has the potential to sequester an additional 267 million tonnes CO2e in forests of the United States, second only to reforestation among natural climate solutions[i]. IFM offers an important way to fund forest resilience and restoration work, such as fuel breaks, thinning, or balancing of age classes, while also reducing and removing carbon emissions.

ACR is the leading carbon crediting program for North America, with IFM projects covering over 8 million acres of forestland in the U.S. and Canada.

ACR first introduced its IFM methodology in 2010, and seven updates later, the newly released IFM version 2.1 increases the precision of its requirements for developing and evaluating conservative baseline scenarios.

Key takeaways about ACR’s updated IFM methodology include:

- The updated IFM methodology is fundamentally the same workable approach that has been applied to millions of acres of forests across the United States and Canada, incorporating over a decade of experience and leveraging the availability of new technology.

- The updated IFM methodology meets market expectations for quality through enhanced requirements for rigor and precision.

ACR achieved these objectives related to workability and precision through a couple key innovations:

- A baseline setting and updating process where key parameters are calculated with robust assumptions ex ante (up front) and verified ex post (after the fact), prior to each credit issuance.

- A systematic deep dive into the specific conditions of each property to understand the ability and intent of a landowner to harvest timber.

The quantity of credits issued to a carbon project is based on the difference in carbon stored between business-as-usual management (i.e., the “baseline”) and with-project management. As a result, setting high-integrity baselines is an extremely important component of carbon crediting.

ACR has been thoughtful and responsive in regularly refining our IFM approach based on lessons learned from implementation and demonstrated best practices. We strive for high-quality.

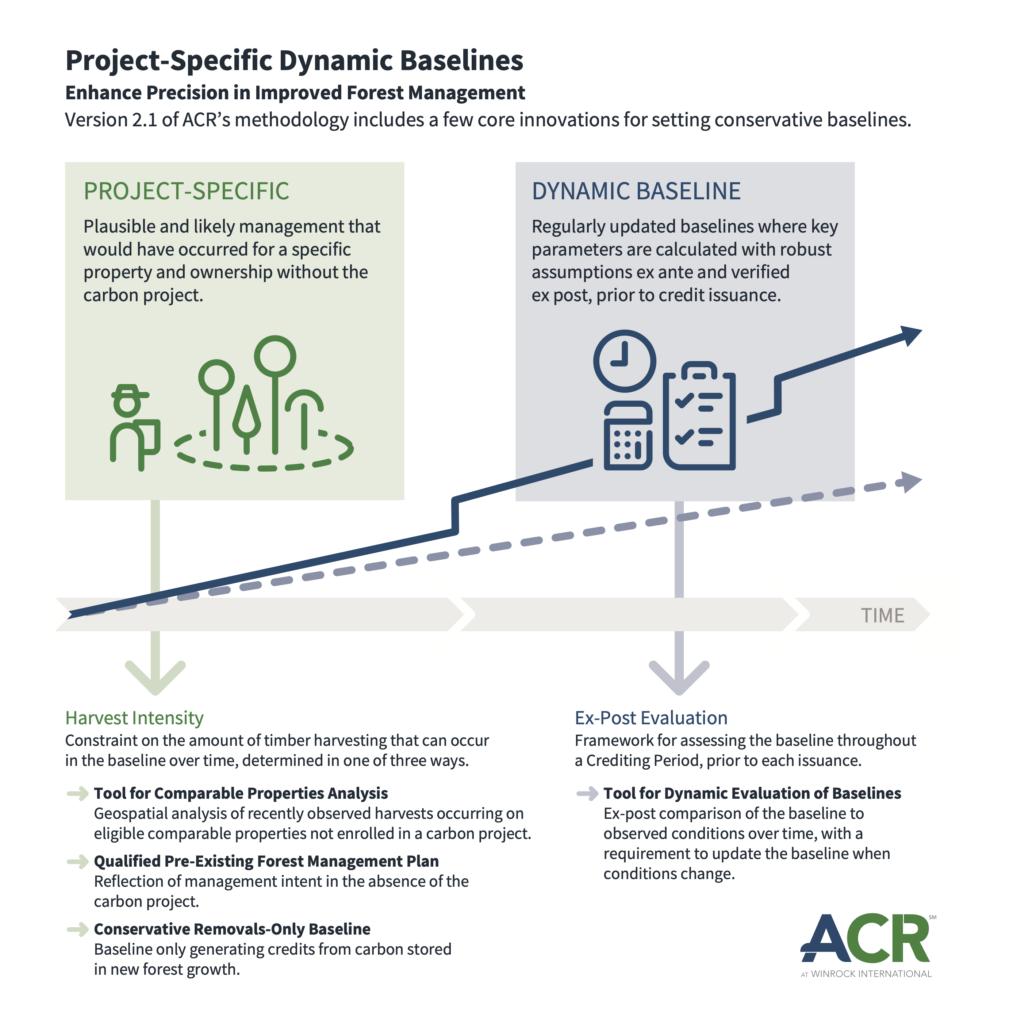

This article focuses on a few of the core innovations in the recent update to our methodology as they relate to a key concept, Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines.

ACR’s Approach to Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines

ACR Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines use information derived from the project area to set a precise and conservative carbon crediting baseline. The approach requires projects to reassess and update baselines as necessary – prior to each credit issuance.

“Project-specific” emphasizes the plausible and likely management scenario that would have occurred for a given property and ownership, had the carbon project not been undertaken.

This requires detailed information regarding the ability and intent of a landowner to harvest timber. For example, a nonprofit land trust is likely to have a different intent for its property compared to a forest management company; the baseline should reflect those differences. Similarly, a landowner without merchantable or accessible trees shouldn’t be credited for deferring a harvest that could never feasibly occur. ACR’s approach requires a comprehensive evaluation into the specific conditions of each property to provide the details needed to understand the plausible and likely baseline scenario.

“Dynamic” emphasizes a baseline that is regularly updated to reflect changing conditions over time. The ACR IFM baseline is calculated with robust assumptions ex ante and is confirmed and updated ex-post on the basis of observable, pre-determined parameters relevant to forest management. While “dynamic baselines” have been proposed in the carbon market across a variety of contexts, the ACR approach was designed to reflect changing conditions and increased ambition over time. ACR IFM baselines are evaluated prior to each issuance to confirm the baseline remains relevant and accurate across the lifetime of the project.

The latest iteration of the ACR IFM methodology implements this approach with two important updates: 1) a new “dynamic evaluation” of baselines over time; and 2) the addition of “harvest intensity” as a constraint in baseline setting. These updates are presented below.

Reflecting Changes on the Ground

Carbon credit buyers have signaled a desire for more frequently updated baselines. This raises a challenge in balancing the certainty needed for attracting upfront investment for landowners to commit to long-term harvest management practices with the flexibility necessary to modify baselines when conditions change. The ACR IFM methodology embraces this balance in a practical way to produce high-precision, high-impact carbon credits.

To determine if a project baseline must be updated, ACR developed the Tool for Dynamic Evaluation of Baselines. The tool establishes a framework for assessing the baseline throughout a Crediting Period on an ex-post basis, prior to each credit issuance.

At each Reporting Period verification – full and desk-based – an ex-post comparison of the baseline scenario to recently observed conditions is conducted. The comparison is implemented as a practical checklist which assesses key parameters, requiring projects to demonstrate that baseline assumptions and harvest rates align with relevant observed legal, physical, and economic conditions. If parameters have changed significantly, the baseline is adjusted prior to credit issuance.

In addition, for each Reporting Period subject to full verification, occurring no less frequently than every five years, a complete reassessment of the long-term modeled baseline scenario is also conducted and modeled projections are refreshed and re-parameterized.

Importantly, ex-ante projections do not define the baseline scenario for crediting purposes. ACR only issues ex-post credits, following an assessment of modeled versus observed conditions at each verification preceding credit issuance.

Setting a Precise and Conservative Baseline

All ACR IFM projects must conduct a robust forest inventory to help determine the baseline. Foresters assess the conditions of the property, physically measure trees, and summarize the available forest resources. Only merchantable and accessible trees may be considered for harvest in the baseline. All baseline harvests must be legally, physically and financially feasible, factoring in specific costs and logistics relevant to the property. Simply put, there is no substitute for boots-on-the-ground observations and data.

Projects then develop a realistic and likely forest management trajectory that would occur in the absence of the project, which involves two steps. First, projects must specify silvicultural prescriptions that are common practice for the region and appropriate and likely for the project area, given its species mix, terrain, and other characteristics. These prescriptions must be substantiated by a local forester.

The projects then calculate harvest intensity, which is a constraint on the amount of harvesting that can occur in the baseline over time, expressed as the maximum percent biomass removed per acre per year. Essentially, the baseline can only be as aggressive as the observed harvest intensity occurring on nearby comparable properties with similar characteristics and land ownership type, but not enrolled in a carbon project.

Ultimately, there are many factors that may impact the volume and type of forest products a landowner would harvest, and they may change over time. Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines consider forest conditions, site access and operating costs, mill access and capacity, legal conditions, and more, to provide the best possible information for assessing what a landowner would most likely do in the absence of the carbon project. This is all vital to establishing a credible and conservative baseline.

Harvest intensity conservatively ensures that baselines reflect variables that are otherwise hard to measure, such as landowner intent and broader market conditions. The approach requires Project Proponents to prove out baseline harvesting levels, while also safeguarding against unrealistically aggressive baselines.

Calibrating Baseline Harvest Intensity

The ACR Tool for Comparable Properties Analysis prescribes a detailed geospatial analysis for calculating harvest intensity from recent observed harvests occurring on similar properties in the region that are not enrolled in a carbon project. Projects may use publicly available, pre-approved harvest detection data sources, or may propose an internally developed and calibrated remote sensing model if accompanied by a demonstration of increased precision in comparison to the pre-approved approach.

To conduct a comparable properties analysis, eligible properties are identified using cadastral data (i.e., tax parcel boundaries) and eligibility criteria. Eligible comparable properties must be of a similar size and forest cover class as the project and be located within a 150-mile radius. They must also have a similar ownership structure (non-profit, public, private industrial, family forest owner, etc.). Eligible comparable properties are stratified by forest type, and their recently observed harvests and forest conditions are mapped using remote sensing.

ACR then requires projects to systematically evaluate each property across seven key parameters, including property size, distance to the project area, slope and elevation, aboveground biomass density and merchantability, and forest type. A similarity index ranks the comparable properties, and the eight most similar are considered “matched.”

Matched properties are then subjected to an outlier detection test, and of the remaining matched comparable properties, one is selected as a representative harvest constraint. This means that baselines may only be as aggressive as the observed harvest intensity occurring on the most similar nearby properties, within a recent lookback period, that are not enrolled in a carbon project.

In addition to the comparable properties analysis, the ACR IFM approach also includes two additional pathways to set harvest intensity: a qualified, pre-existing forest management plan, or a conservative removals-only baseline.

Qualified, pre-existing forest management plans must have been prepared by a professional forester prior to carbon project development, reflecting management intent in the absence of the carbon project. The qualified management plan must contain specific recommendations for the spatial extent or volume of biomass to be removed over time. These recommendations are used as a maximum baseline harvesting constraint.

Removals-only baselines must develop and validate a baseline harvest schedule, considering all constraints to forest management. If the modeled baseline harvests more than growth, the baseline is conservatively set at initial carbon stocks. If the resulting baseline harvests equal or less than growth, the modeled baseline can be used. As the name suggests, removals-only baselines do not generate emission reductions credits (only removals) and must conservatively be held at initial carbon stocks or increasing.

With ACR IFM projects covering millions of acres of forestland in the U.S. and Canada, including small family woodlands and tribal lands, it is important to give landowners options, especially for an innovative approach.

Whether through the comparable properties analysis, qualified forest management plan, or removals-only baseline, the harvest intensity constraint establishes an accurate and conservative baseline.

Conclusion

To achieve the Paris Agreement goals, carbon markets must grow. To grow, carbon credit buyers demand high integrity, while landowners and project developers require practicality and predictability before signing an agreement that legally binds their forest management for a minimum of 40 years. Since an independent carbon crediting program is only as beneficial as it is used, ACR’s job is to find the right balance between these interests.

ACR Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines represent this balance. They are set based on observed management occurring on similar, nearby lands that are not enrolled in a carbon project. Baselines are updated over time to reflect observed conditions changing in the project area and surrounding landscape. And they are regularly reassessed to ensure ongoing validity prior to issuing credits at each verification.

The ACR Improved Forest Management Methodology version 2.1 represents the latest iteration of our widely used approach to promote sustainable management of forests above common practice.

Through this approach, ACR provides landowners with a meaningful and practical way to manage their lands with climate at the forefront. Hundreds of landowners are already enrolled in IFM carbon projects with ACR. These landowners have realized the benefits of embracing carbon as an amenity and revenue stream that can finance their long-term forest management objectives.

As the leader in North American IFM, ACR has continually set the bar for quality in the market. Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines now move the market a step further in ensuring conservative and data-based IFM carbon crediting.

ACR looks forward to continuing our work with landowners, project developers, credit buyers, and the market overall in incentivizing the climate benefits needed to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement and ensure a stable, livable climate.

July 2025: ACR posted an explainer video for application of dynamic baselines under ACR’s U.S. IFM methodology v2.1.

July 2025: Projects listed under previous versions of ACR’s U.S. IFM methodology and Canadian IFM methodology can now optionally use the Dynamic Evaluation of Baselines Tool version 1.1 to perform dynamic baseline evaluations on a go-forward basis.

On September 19, 2024, we hosted a webinar about ACR Project-Specific Dynamic Baselines. If you would like to watch it, a recording is available here and you can download the slide deck here.

Kurt Krapfl is forestry director at ACR.

[i] Fargione et al., 2018. Natural climate solutions for the United States. Science Advances 4(11). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aat1869