This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

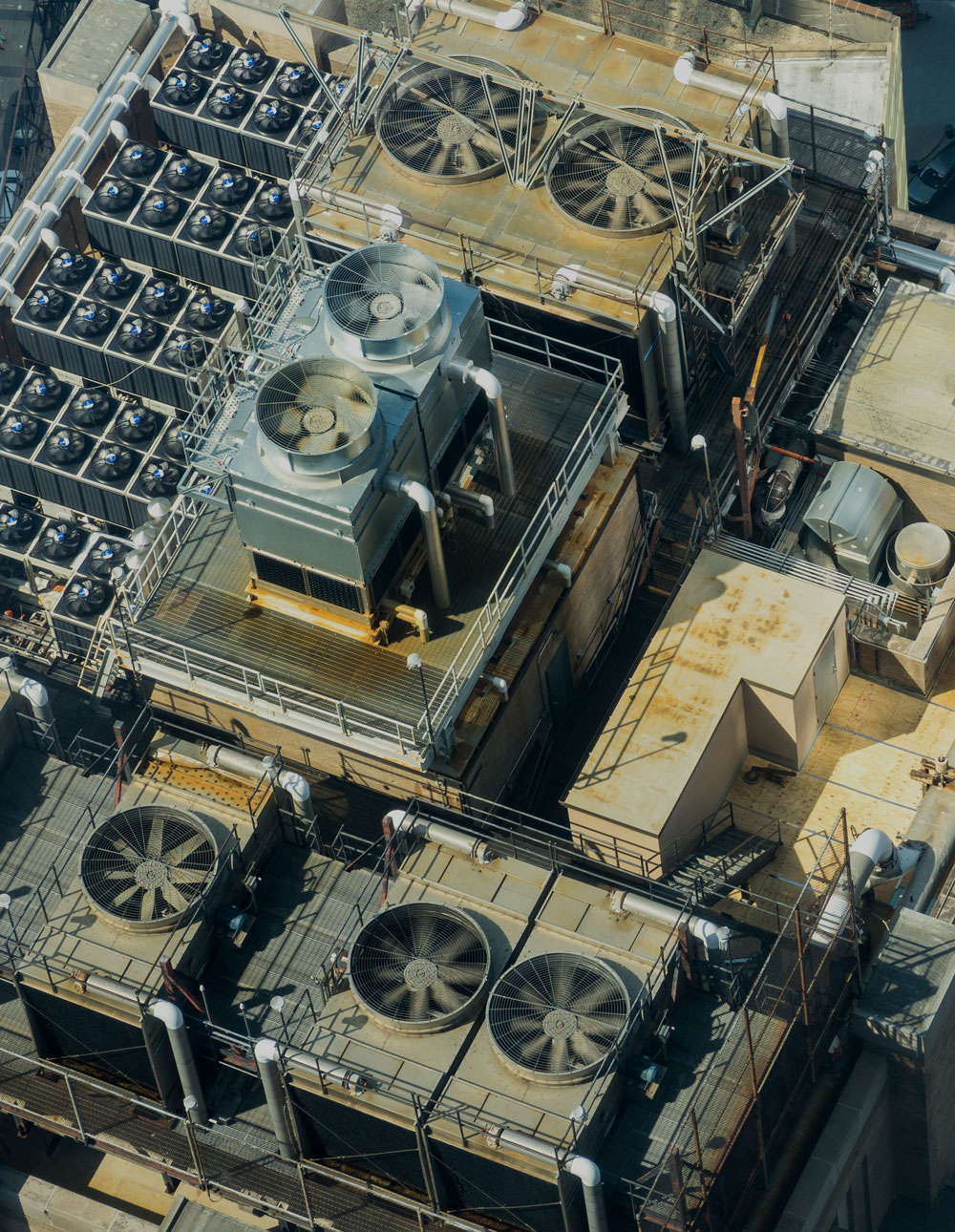

Our old fridges and air conditioners are still emitting super pollutants–and their climate impact is equal to the emissions of the entire country of Switzerland

By Megesh Tiwari

Originally published in Fortune.

A recent academic study made an alarming finding: The level of several ozone-depleting substances, which are meant to be regulated under a groundbreaking global agreement, are actually increasing in the atmosphere.

Let’s be clear: The Montreal Protocol–the late ‘80s international treaty that aims to protect the ozone layer of the atmosphere by phasing out the production and consumption of ozone-depleting substances (ODSs)–has been a huge success overall. The levels of many ODSs have been reduced, and the ozone is recovering. That’s why the study’s finding that atmospheric concentrations of five ozone-depleting chemicals are at a record high is so surprising.

Specifically, this refers to five kinds of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). CFCs are entirely man-made gases used in a variety of applications, including refrigeration, air conditioning, and as chemical solvents. In addition to the damage they cause to the ozone layer, CFCs also happen to be extremely dangerous climate pollutants capable of producing up to 10,000 times the global warming potential of CO2. Most experts believe the Montreal Protocol would by now have phased down CFC production to a point where we are seeing reductions in the atmospheric levels of all compounds.

Unfortunately, the study shows this has not occurred. Over 30 years after the Montreal Protocol came into effect, the atmospheric levels of several compounds are higher than they’ve ever been. This is a big problem as the CFCs identified in the study had a cumulative warming effect in 2020 that was on par with the total CO2 emissions of the country of Switzerland.

While the researchers behind the study identify some possible answers as to why CFC levels are increasing, there are still gaps in our knowledge. What we do know from the study’s findings is that we need to act rapidly to get back on track. Things might be looking better for the ozone layer, but there is still a big climate problem that needs to be addressed.

While the Montreal Protocol banned global production and consumption of virgin CFCs, existing stockpiles of CFCs (that were produced before the ban and that continue to be used for old equipment), can still be recovered, reclaimed, and reused. While recovery and reuse are good, the reclaimed CFCs are often used in old equipment that leaks heavily. Each time the recovered CFC is reused, a significant percentage of it leaks into the atmosphere. This can be one reason for the increase in certain CFC levels as more equipment ages.

Another reason is likely the indefinite stockpiling of CFCs (either virgin or recovered) in poorly stored tanks that eventually rust and leak. As more equipment reaches end-of-life and demand for both recovered and virgin CFCs decreases, stockpiles increase and eventually leak. This situation is worse in developing countries with poor recovery and storage capabilities. As these stockpiles age, we can anticipate increased leakage going forward. Currently, only a handful of countries require the destruction of these end-of-life CFCs.

The only solution is to properly destroy stockpiles of CFCs. There are methods of doing so that ensure CFCs don’t reach the atmosphere. However, the process is expensive–and even more so in developing countries where collection is difficult.

To succeed, the world needs to get serious about increasing our capabilities to monitor CFCs and other similar compounds in our atmosphere and identify their sources. We also need to build up the infrastructure to handle and destroy these compounds and train a highly skilled workforce to carry out the job. In other words, we need to create more demand and drive finance towards these solutions.

This is something carbon markets can help achieve. They have the potential to offer one of the only sustainable sources of finance to fund and, therefore, incentivize the collection and destruction of CFCs stockpiled across the globe. While there has been much discussion of using instruments like carbon credits to focus on biodiversity, there is much less attention paid to other carbon market solutions like CFC destruction.

Carbon finance can allow companies to hunt for CFC stockpiles around the world. It can help governments that haven’t had the funds to destroy the stockpiles to finally do so and encourage entities that have been stockpiling CFCs to search for partnerships with other companies and destruction facilities to destroy them. In short, carbon finance can accelerate the collection and destruction of CFCs and help solve a problem that still persists despite the Montreal Protocol’s ban almost three decades ago.

The resulting carbon credits are of high integrity as there is a clear case of additionality, the emission reductions are permanent, and there is little concern that reducing CFC usage in one area would cause it to increase in another. While we were the first to issue such credits, we encourage others to follow suit.

We need to tackle super pollutants like CFCs over the coming years to save us from decades of more severe climate change consequences. Catalyzing action through carbon markets can help accelerate the timeline toward achieving all the ambitions of the Montreal Protocol.

Megesh Tiwari is a senior technical manager at American Carbon Registry.