This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Cleaning up global cooling systems with carbon markets

By Megesh Tiwari, Senior Technical Manager

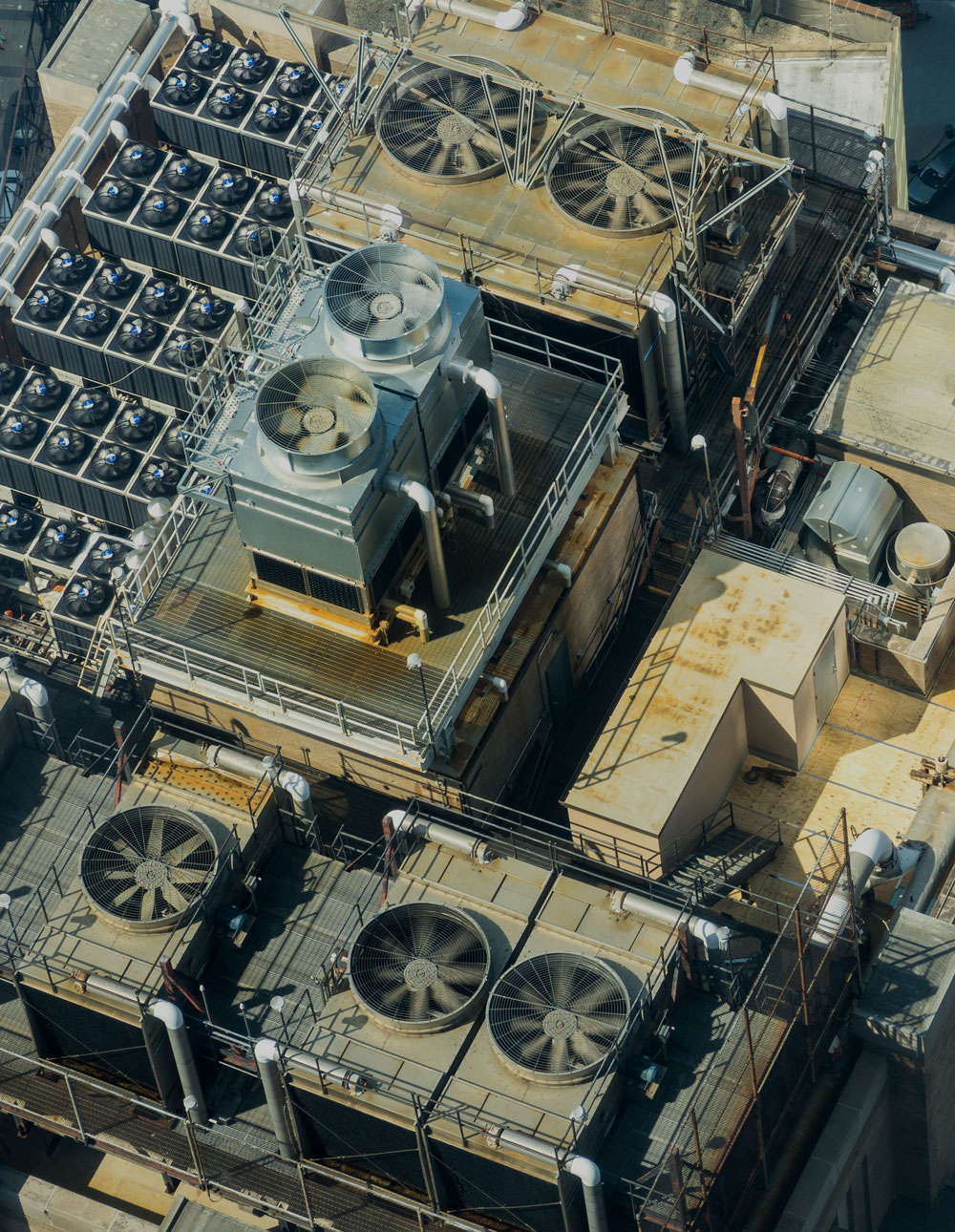

Refrigerants are the chemicals used in our air conditioning and refrigeration systems to keep people, food and medicine cool. In an increasingly warming world, they are being utilized more and more to help people adapt to rising temperatures.

Unfortunately, the most common chemical compounds we use as refrigerants, such as hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), are extremely potent greenhouse gases (GHGs); many trap thousands of times more heat in the atmosphere than CO2 over a 100-year period. We also still face a serious legacy issue around older refrigerants like HCFCs and CFCs, which are also ozone depleting substances (ODS).

All told, these climate-warming refrigerants slowly leak into the atmosphere throughout production, use and disposal. Worse still, sometimes they are deliberately vented during servicing or disposal of equipment, although certain countries ban this practice. As equipment reaches end of life, there is dwindling use for the remaining refrigerants. Because destruction of the refrigerants is not mandated, unused supplies can be stockpiled for long periods, over which time the pollutants leak into the atmosphere.

It is estimated that across the U.S. the installed base of these super pollutants is equivalent to 3.6 billion metrics tons of CO2e emissions. Globally, it’s 24 billion metrics tons of CO2e. With increasing demand for air conditioners and refrigeration units, they could account for roughly 20% of global climate emissions by 2050.

What’s being done about refrigerant climate pollution?

Under the Montreal Protocol, the production and consumption of CFCs has been phased out by all nations and HCFCs have been phased out by most developed nations. And a global phasedown of HFCs has recently begun under the Kigali Amendment to the Protocol. Its ratification by the United States will certainly have a significant impact on curbing the impact of these refrigerants on global warming. By reducing HFC emissions, it is estimated that up to 0.5°C of global warming could be avoided by 2100.

However, there’s much more that can be done. When it comes to ODS, many continue to be legally reclaimed and recycled for use in older equipment that is prone to more leaks. The Montreal Protocol also doesn’t address the millions of HFC units already being used and sold in today’s market. For example, by 2050, the current HFC phase down schedule will have allowed 3.6 billion CO2-equivalent metric tons to be sold into the U.S. market, effectively doubling the potential climate harm these super pollutants can cause in the coming decades.

What can be done to take refrigerants out of circulation today?

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) has proposed a range of commonsense actions to improve lifecycle refrigerant management. Outlined in their 90 Billion Ton Opportunity Report, these actions focus on avoiding and reducing refrigerant leaks, promoting refrigerant recovery, and increasing reclamation rates to mitigate unnecessary refrigerant use and emissions.

These are all no-regrets, high-impact solutions that warrant immediate support, both in terms of regulation and voluntary action. However, in the absence of additional regulation, it all comes down to incentives. And the report overlooks a key ingredient that can help provide those incentives: carbon finance.

Simply put, carbon markets can be a powerful tool to catalyze and accelerate adoption of the actions recommended in the report. ACR’s ODS destruction, HFC reclamation, Advanced Foam Blowing Agent and Advanced Refrigeration System methodologies, for example, are already incentivizing and encouraging many of these actions.

What does this look like in practice? Take for example a joint initiative between Therm and the North American Sustainable Refrigeration Council (NASRC). Under this initiative, financing from the sale of carbon credits, using ACR’s Advanced Refrigeration Systems (ARS) methodology, is allowing mid-sized grocery retailers and foodservice providers to make the switch to more sustainable low-GWP refrigerant compounds cheaper, and therefore faster, than without the carbon market.

Destruction of ODS and HFC refrigerants is costly. Without revenue from the sale of carbon credits, there would be no sustainable source to finance destruction. This would lead to more stockpiling and eventual leakage of these high-GWP climate pollutants in the atmosphere.

Another example comes from the California Air Resources Board’s (CARB) Refrigerant Management Program. This program requires companies to track and report their refrigerant emissions and incentivizes the use of more sustainable refrigerants through a credit trading system. Since its implementation in 2011, the program has helped reduce refrigerant emissions in California by more than 30%.

What can be done to grow the carbon market supply and demand for refrigerant credits?

Currently the carbon market for refrigerants faces several solvable challenges. These include inadequate capacity of infrastructure and associated trained workforce to help reclaim and destroy high-GWP pollutants. There are high capital costs to build the facilities and the train staff necessary to undertake this technical work. Additionally, there is a lack of awareness among buyers of carbon credits that these types of projects exist. To be frank, many buyers, when they think of carbon markets, think about renewable energy or forestry projects.

Carbon credits generated from the management of high-GWP refrigerants are of high quality because they are proven to be highly additional and permanent. These high-quality credits demand higher carbon prices to motivate maximum action from manufacturers and companies involved in servicing, reclaiming, and destroying these refrigerants. With many high-GWP refrigerants also being short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs), paying higher prices for refrigerant carbon credits, is also justified by their higher contribution to reducing GHG emissions (and hence global warming) in the near term (by mid-century) which aligns with most net-zero targets. Higher carbon prices for high-quality refrigerant carbon credits would help significantly lower GHG emissions and provide the volume of credits needed by buyers to offset emissions to meet mid-century net zero targets.

High-GWP refrigerants should be replaced with low-GWP alternatives, recycled and reclaimed for reuse, or destroyed. No high-GWP refrigerant should be allowed to leak into the atmosphere due to lack of incentive to do so. This would be too costly for the planet. At the moment, the rates at which high-GWP refrigerants are being replaced with lower GWP alternatives in most end-uses like supermarkets and grocery stores, and HVACs, reclamation of used High-GWP refrigerants, and destruction of High-GWP refrigerants are all very low. Buyers of carbon credits need to realize this massive climate problem associated with the continued use and leak of High-GWP refrigerants. The carbon market can provide the much-needed incentive to motivate action to lower use and leak of these super pollutants. At adequate carbon prices, emissions reduced from increased refrigerant management can be a significant source of high quality, highly additional and permanent carbon credits that can help buyers meet their net zero and other climate targets by the midcentury.

With carbon markets expected to grow significantly, there are positive signs that these challenges can be overcome. Higher demand and prices for carbon credits will increase the attractiveness of financing the recovery, reclamation and destruction of high-GWP refrigerants. It would benefit stakeholders in the carbon market space and those who care about the climate impact of refrigerant compounds to look more closely at how carbon markets can be an effective tool to motivate action.